Rhetoric is all over the news right now.

No, not the rhetoric itself, but the word “rhetoric” as people use rhetoric to discuss the concept of rhetoric. And if that seems confusing, that’s kind of the point.

If you listen to politicians and pundits, the term rhetoric might be interpreted to just mean “speech.” It might be the words we use or the discussions we have or the articles we read. And, sure, OK, that’s part of it.

Rhetoric, like many words, has different definitions. It can be simply the skill or art of communication. It’s how we build our points in conversations and how we construct our arguments in debate. It includes the devices we use to do that, like the rhythm built into a speech or the deliberate inflation (hyperbole) or reduction (litotes) of an element’s importance.

Then there is rhetoric as a style of speech. Rhetoric can be the language we use to achieve a specific goal. Sometimes it’s sympathetic, like a commercial trying to get you to donate to a good cause. Sometimes it’s self-righteous, like a canceled celebrity defending himself on YouTube.

But probably the best recognized rhetoric is incendiary — an attempt to inflame passions of the audience not for something, but against someone. We recognize it because we hear it so very often.

Our politics drip incendiary rhetoric like high-fructose corn syrup — clear and sticky and with no real nourishment. The candidates repeat it on a loop. Cable news channels are known for it, with some devoting prime time news blocks to nothing else.

And who hears it? Everyone. Impressionable kids. Frustrated adults. Angry people who want a target for their rage. Incendiary rhetoric doesn’t light a quick burning match that can burn the fingers before it snuffs out. It lights a wick that can burn long and steady before touching off a firestorm.

That is something we have definitely seen this summer. Former president and GOP nominee Donald Trump has been the target of two assassination attempts — one that resulted in bloodshed and death.

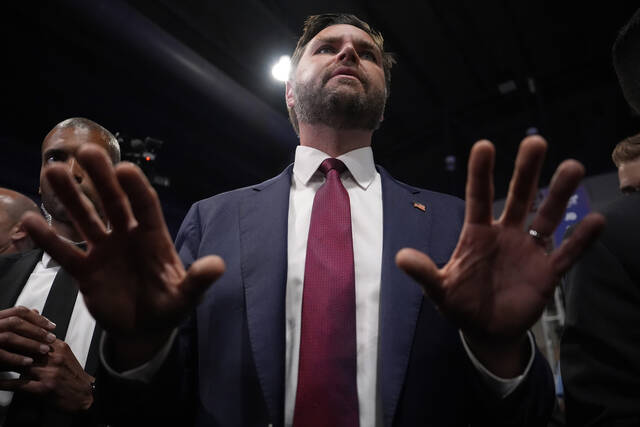

His running mate, U.S. Sen. JD Vance, R-Ohio, has pinned that on Democrats, despite the Butler County shooter, Bethel Park resident Thomas Crooks, being a registered Republican and the more recent thwarted gunman, Ryan Routh, being a 2016 Trump voter.

“Somebody’s gonna get hurt by it,” Vance said.

People are hurt by violent rhetoric every day. It is not just something that happens to political candidates. It happened in 2019 when Patrick Crusius went to an El Paso, Texas, Walmart inflamed by anti-Latino hatred, leaving a blueprint for his actions that cited far-right Great Replacement theory. There were 23 people killed and 22 injured.

It happened in 2022 when Payton Gendron, 18, livestreamed his murder of Black shoppers at a Buffalo, N.Y., grocery store. Gendron made sure people knew why — again citing Great Replacement theory.

And it happened in 2018 in Pittsburgh when Robert Bowers, whose social media presence cited conspiracy theories about a Jewish organization aiding Central American “invaders,” posted “Screw your optics, I’m going in.” He then headed to the synagogue where three congregations were at worship and committed the deadliest antisemitic attack in U.S. history.

Vance is not wrong. Someone is going to get hurt. Again. Every day that violent words drip from political tongues, people will get hurt.

And it is on everyone with a platform to stop the rhetoric.