Americans need to change their behaviors in advance of the holidays unless they want a very grim start to the new year. If we don’t, cases of covid-19 could overwhelm the health care systems in many regions in the country and deaths will continue to escalate. Without significant changes to our collective behaviors, we should expect more than 3,000 deaths per day — more than the number of people who died in the 9/11 attacks.

Small house parties have been shown to be one of the major factors resulting in the spread of the disease. These types of gatherings are likely to dramatically increase as the holidays get closer. Every family should seriously consider limiting their holiday and new year celebrations to their nuclear family alone.

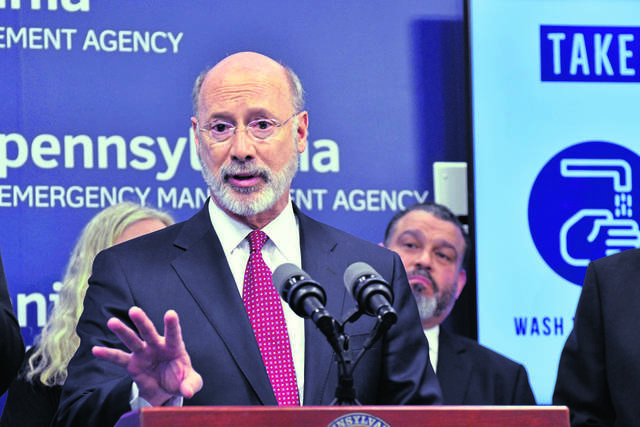

At this point in the pandemic, nearly one in every 1,000 people in the country has died from covid-19 — and that number continues to grow. In response, throughout the country, state and local governments are reenacting restrictions to try to slow the spread of the disease. Pennsylvania is the latest, enacting a three-week business shutdown. These restrictions are unfortunate but necessary.

Critics of restrictions including “lockdowns” have argued that these orders are an infringement on their individual liberties and a violation of their rights. What these individuals don’t understand is that state and local officials often have no choice. The reason is simple: The U.S. does not have the health care capacity to withstand a prolonged public health emergency that uses significant health care resources.

The U.S. spent the last decade in the relentless pursuit of efficiency in its health care system. These efforts were successful in eliminating unused hospital beds throughout the country. The challenge we now face is that the U.S. has very few hospital beds to spare.

The U.S. currently has approximately 2.8 beds per 1,000 population. On any given day — prior to covid-19 — two-thirds of these beds were in use. Thus, the U.S. has an available bed capacity of less than 1 bed per 1,000 population. To put this number into perspective, countries like Japan and South Korea have over 12 hospital beds per 1,000 population. The U.S. has fewer hospital beds per capita than most countries in Europe and many smaller, less developed countries around the world.

In addition — prior to covid-19 — the U.S. was continually addressing health care workforce shortages. For example, the U.S. has approximately 2.6 physicians per 1,000 people compared to over 4 physicians per 1,000 people in countries like Italy, Germany and Switzerland. The shortage of physicians in the U.S. is projected to continue to grow to over 100,000 in the next decade. We also have shortages of health care workers in critical areas needed to respond to the pandemic such as respiratory therapy. This is why many regions in the country are experiencing significant burnout and exhaustion from health care workers.

The reality is that young otherwise healthy individuals represent a large number of hospitalizations for covid-19. As these individuals require a significant number of hospital beds around the county, it stresses our health care system’s ability to provide care to individuals who need urgent care because they were in a car wreck or because they are experiencing an acute health care problem like a heart attack.

To save our health care systems and the many brave and selfless people that work in them, we need to limit our holiday celebrations to our nuclear families. Doing so will allow us to bring in the new year knowing that we all did everything we could to support health care workers in their efforts to save lives and ensure they have the capacity to serve every person who needs care.

David Dausey, Ph.D., an epidemiologist, is executive vice president and provost at Duquesne University and a full professor in Duquesne’s John G. Rangos Sr. School of Health Sciences. He is also a distinguished service professor of health policy at Carnegie Mellon University.