On April 12, 2005, I found myself at the Cathedral of Learning with students of mine from the University of Pittsburgh interviewing those who had worked with Dr. Jonas Salk to develop a vaccine that would conquer the most feared disease of the 20th century — polio. During that anniversary celebration, I would hear countless tales of people who worked with Salk in his lab, pipetting a deadly polio virus by mouth, and who had offered their arms for a then-experimental vaccine that no one could assure them at the time was “safe” or “effective.”

In fact, just a decade earlier, a previous polio vaccine had killed people. But everyone was so motivated by the fact that each summer, pools would be closed, along with movie theaters, and kids were not allowed to go to each others’ birthday parties because of the fear of the crippling polio virus.

These stories were so extraordinary that I spent years producing a film, “The Shot Felt Round The World,” which was eventually broadcast on the Smithsonian Channel and the BBC. It included an interview we did with Bill Gates, who was working with Rotary International trying to eradicate polio as has only previously been done with one other disease, small pox.

This film captured renewed interest in the aftermath of the covid-19 pandemic after a piece I wrote, “The Deadly Polio Vaccine and Why It Matters for Coronavirus,” went viral, leading to me being interviewed for “CBS Sunday Morning” with Paul Duprex, the Jonas Salk chair of the University of Pittsburgh’s virology lab. That led to its own documentary, “Chasing Covid,” trying to remind the public of how vaccines have saved more lives than any other scientific development in human history at a time when vaccines were again facing public skepticism.

As another anniversary of this medical miracle of last century approaches, memories of those “Pittsburgh polio pioneers” I talked two almost 20 years ago have rushed back, as my own doctor, Dr. Mike Finikiotis, has reunited me with the daughter of one of the many extraordinary people I met during the 50th anniversary celebration.

John Troan was a young reporter for The Pittsburgh Press working on the science beat when he got a tip from Dr. Campbell Moses, working in a University of Pittsburgh lab, to go visit a “whiz kid” named Jonas Salk, who William McEllroy, dean of Pitt’s medical school, had brought in from Michigan to do research. “Tell him Moses sent you,” Troan recalled half a century later. In several filmed interviews, Troan described for me his lifelong friendship with Salk, admitting he was trepidatious about going to Salk’s virus lab at first. He had good reason, as his daughter, Mary Lou, reminded me how many of her father’s siblings had died in infancy, at a time when infectious disease killed millions — causing more casualties from the Spanish flu than occurred in World War I.

Helping Troan overcome his fear of catching something in Salk’s lab, Troan’s own physician, Dr. Ruben Snyderman, reassured him he would be OK.

As I spoke to Mary Lou, I was reminded of details her father recounted for me that have their own lessons for today. When John Troan first met Salk, he had come to Pittsburgh to work on a vaccine for influenza. Salk was wary of the press, but tested Troan, giving him a chance to write about experiments he was conducting on a flu vaccine he was doing with 15,000 soldiers at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Salk was impressed with Troan’s accuracy of reporting, and hence by the time he began working on a polio vaccine with funding from the March of Dimes, the scientist had already begun to trust the reporter.

Salk was close-mouthed when his vaccine research shifted from the lab, where he had proven the vaccine had worked on monkeys, to trials involving human subjects. But Troan figured out he was doing these early tests on children who already had polio living at the D.T. Watson Home for Crippled Children in Sewickley. Salk had slipped, mentioning something about how things were going well “out there,” causing Troan to deduce Salk was working with Dr. Jesse Wright, the medical director of D.T. Watson who also was in charge of the polio ward at Pitt’s Municipal Hospital.

At D.T. Watson, Troan would learn about how Wright and Salk had arranged to have his polio vaccine tested for the first time on these children, including 2-year-old Ron Flynn, who later recalled being pushed onto the floor by Wright so he could learn to get up and be independent; 10-year-old Jimmy Sarkett, whose name would be used in the Salk lab to identify one of the strains of the polio virus; and a teenage Bill Kirkpatrick, the first human who volunteered to be tested for this vaccine that, even if it worked, would never help him or others who had already had the disease, but would prevent other kids from getting it.

Soon the vaccine was to be tested on healthy children. Troan described how he met Salk at a Chinese restaurant in Oakland and worked with him on language for a release that parents would have to sign to have their children get this still very much experimental vaccine. Unlike today’s pages-long disclaimers, this document was the size of a postcard, giving Salk permission to inject children at local schools.

Salk had confidence the vaccine would work, having at this point tested it on his own three sons, including 10-year-old Peter, who would grow up to be an accomplished scientist himself working with his father on an AIDS vaccine at the Salk Institute, and his youngest, Jonathan, who was forced to pose for a publicity photo of him getting the shot from his father with his mother, Donna, looking on. He was clearly terrified as any 4-year-old would be, and who perhaps not coincidentally would become a child psychiatrist.

As word spread that the Salk polio vaccine, using a “killed virus,” which went against the medical orthodoxy of its time, was working, Salk was pushed out to the public by Basil O’ Connor, FDR’s lawyer, who started the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. The likable young scientist became the reluctant face of this new vaccine. Some of his peers would accuse Salk of seeking the limelight, but Troan told me how Salk had asked him to refer to it not with his name, but as the “Pitt vaccine.”

But America wanted a hero. In the summer of 1952, polio cases had spiked to an all-time high, with newspapers aound the country printing the number of polio cases on front pages like they were baseball box scores. Parents were praying for some medical miracle which would spare them the horrors of this unseen virus that was crippling their children, leaving them on crutches, in wheelchairs or in the dreaded iron lung, and in some cases, taking their lives.

I got a personal sense of this when Pittsburgh philanthropist Elsie Hillman told me how she had volunteered her own children for the early trials in October 1953. She remembered the date; she had been playing tennis with her best friend, Polly Off, who had complained of feeling fatigued, and the next day ended up in an iron lung. “Dearie,” she recalled when I interviewed her for our documentary, “I was no hero. We were all so terrified. Anyone would have done it.”

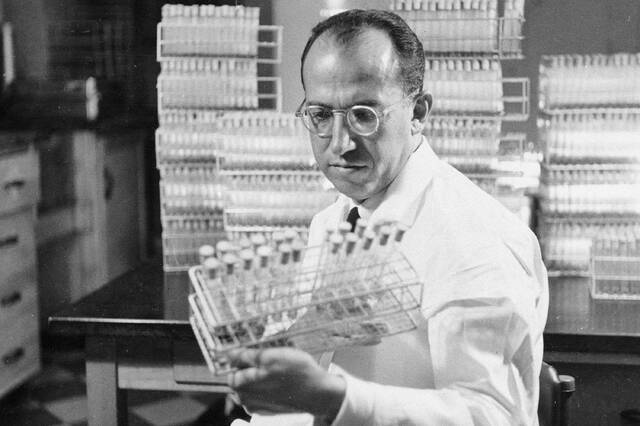

It was John Troan who covered this all for The Pittsburgh Press, and, as media interest grew, who had persuaded Salk to let a national reporter do a story and take photos of him in the lab. Salk did not want to give up valuable time, as he was in a race against the disease, but agreed as a favor to Troan. He held up some glass containers with the polio virus while posing, one of which broke, causing Troan a few sleepless nights, worrying he may have contracted the disease and might give it to his own young children. Troan admitted he always took a shower when he came home from visiting the lab, though he knew the polio virus could not be washed off.

Ethel “Mickey” Bailey, who had worked in the Salk lab, recalled getting a mouthful of polio virus once when pipetting and praying that she would not get polio. Remarkably, neither she nor any of the Salk lab workers ever got polio in their years doing this research.

In 2005, I sat watching the 50th anniversary program with Dr. Randy Juhl, former dean of Pitt’s School of Pharmacy and then vice chancellor of the university, who was responsible for research oversight. During the symposium where Dr. Peter Salk paid tribute to the entire team who worked closely with his father on this work, Juhl whispered to me that given today’s regulatory environment, it would have taken at least twice as many years as the six it took the Pitt virus lab to develop their vaccine (which makes the design, testing and distribution of the initial covid vaccines in 18 months all the more miraculous).

After the Salk vaccine had been tested on 7,500 Pittsburgh schoolchildren, the largest medical field trial ever done was conducted, with 1.8 million children around the country participating. The world waited in anticipation for the results of this unprecedented study to be announced at the University of Michigan on April 12, 1955.

Troan recalled sitting in the packed auditorium next to legendary journalist Edward R. Murrow, who asked him what he would have asked Salk if he had gotten the chance. Troan smiled to himself, as he had already written his story, having gotten the scoop days before. When Dr. Thomas Francis announced to the audience that the Salk vaccine was “safe, potent, and effective,” Troan recalled the bedlam that broke out as his fellow reporters screamed “it worked, it worked” as they relayed the news to their papers. It became front-page headlines around the globe, and Salk became one of the most famous men in the world.

Things would never be the same after that moment for Jonas Salk and his family, as Peter recalled his mother being embarrassed by the police escort that greeted them at the airport in Pittsburgh and which took them the wrong way down a one-way street. Salk tried to stay focused on his research, expressing his desire to have an institute at Pitt. He was rebuffed by the school’s chancellor at the time, which might have led to the city being an early leader in biomedical research in the 1960s. But instead, Salk was offered acres by the Pacific Ocean in San Diego, and hence the Salk Institute was built in La Jolla.

Salk had dreamed of harnessing the collective effort that made the polio vaccine possible to conquer other diseases and social problems like poverty. When he gave his last interview near the end of his life in 1994 to Doug Heuck, editor of The Pittsburgh Quarterly, Heuck would recall his take-away being two words Salk had said: “study success.”

Dr. Peter Salk has become a professor at Pitt’s School of Public Health and, as president of the Jonas Salk Legacy Foundation, he donated the desk his father worked at and many other artifacts to the Pitt archives so that others could remember just what is possible when everyone pulls together to defeat a common enemy. Just this week, on April 10, he gave a lecture at Pitt’s School of Pharmacy, which stands where Municipal Hospital used to be with its third floor full of iron lungs and the basement lab between the morgue and the dark room where Jonas Salk began his research.

It is essential this story live on, and not be overly romanticized. Juhl and I co-authored an article on “Lessons from the Polio Vaccine Going From The Lab to the American Public,” which discussed the obstacles and skepticism the Salk vaccine faced even after that 1955 announcement, when later that year less than half of Americans believed in the vaccine. But the proof that the vaccine worked is evidenced by the fact that in 2023 only 374 cases of polio were reported in a handful of countries with the planet being on the brink of eradicating polio forever.

As Jonas Salk said, we need to study this extraordinary success. But the true lesson to be remembered is not just the science, but the spirit of all those who were involved in this effort, volunteering their time and their arms for what was then a risky venture, but what is still one of the greatest medical miracles ever that continues to save the lives of millions around the world.

John Troan lived to be 99, and we all should be grateful for that young reporter who knew how to tell a great story.

Carl Kurlander teaches at the University of Pittsburgh and is a filmmaker and screenwriter whose first screenplay, “St. Elmo’s Fire,” was inspired by Lynn Snyderman, the daughter of Dr. Ruben Snyderman.