Three women and three men serving life sentences in Pennsylvania prisons sued the state Board of Probation and Parole on Wednesday, alleging the state’s refusal to allow a chance at parole to those serving life sentences is tantamount to a death sentence.

The lawsuit challenges a provision in the state’s parole code that keeps the parole board from considering cases in which an individual has been given a life sentence.

The suit was filed on behalf of six inmates who have been serving between 23 and 47 years in prison.

“We are challenging not the formal sentence of life, but we are challenging the restriction of ‘without parole,’ ” said Bret Grote, legal director of the Abolitionist Law Center, which along with the Center for Constitutional Rights and the Amistad Law Project filed the lawsuit.

A spokesperson for the Board of Parole declined to comment on pending litigation.

The lawsuit and the restrictions it targets hinge on the state’s definition of felony murder and the circumstances that dictate whether a murder is graded as a second-degree murder. In Pennsylvania, second-degree murder can be applied when a death happens during the commission — or attempted commission — of another felony.

For example, a robbery that ends in a shooting death can be second-degree murder. A getaway driver or a lookout who didn’t pull the trigger but was party to a robbery that ends in a shooting death can also be charged with second-degree murder.

Marie “Mechie” Scott, 67, has been in prison for 47 years. She was convicted for being a lookout during a robbery that turned deadly. Attorneys on Wednesday played a recorded message from Scott during a virtual news conference.

“I’m guilty of my crime, and nothing can punish me more than I’ve punished myself for what I’ve done,” she said.

She said she hadn’t realized until she was in prison that a life sentence meant she’d never have the chance to even apply for parole, noting “you are sentenced to a life sentence that you must live out until you die.”

The goal for the lawsuit, legally, is for current state parole statutes to be struck down and the Board of Parole be forced to create rules for considering parole for those charged with felony murder, Grote said.

“That’s the legal result,” he said. “The desired result is that Marie Scott comes home to her community.”

Victims’ advocate opposes proposal

Jennifer Storm, acting director of the state Office of Victim Advocate, said her office supports certain types of parole reform. But she said a blanket statute that applies to all types of felony murder would bog down the court system and retraumatize victims and surviving family members.

“That victim and that family member and that family — every year they’d now have to go through a parole process,” Storm said.

If new parole rules apply to anyone convicted of felony murder, she said, it means an application for parole will come every year. She said it will create a constant cycle on cases “that everyone and their grandmother knows would never be released.”

Storm said her office is talking with lawmakers about parole reform that is more specific to certain groups, like geriatric parole. She said they’re also amenable to other specific reforms, such as medical parole and parole specific to veterans. She noted that PTSD “is certainly a factor in criminality.”

“We’re not completely outside the scope of being reasonable here,” she said.

In the virtual press conference, Robert Saleem Holbrook, a former juvenile lifer released in 2018 after 27 years, is now an organizer with the Abolitionist Law Center. He said Storm’s office has weaponized victims’ role in the justice system.

“They tell the victims to come out, share your harm, share your pain, relive your tragedy,” he said. “(It’s) not to heal, but to be in opposition to redemption, to be in opposition to second chances for people who have served decades in prison.”

Storm said such comments must come from a preconceived notion of what her office does.

“We don’t take positions that aren’t in line with the victim we represent – we never have and we never will,” she said.

She pointed to a 2019 survey of 800 surviving family members of victims killed in a second-degree murder. The survey asked about parole reform for those sentenced under the felony murder statute, and about 39%, or around 312 people, responded to the survey.

Of those that responded, she said, 91% were vehemently not in favor.

“It made clear where the numbers fell,” Storm said of the survey. “We provided that documentation to the Legislature. It is not up to us to say what bills go and what bills don’t go. This was one source of information for consideration for the Legislature. To say that we would weaponize victims is wholly inaccurate and incredibly insensitive.”

Woman’s brother slain, son serving life

Loraine “DeeDee” Haw said she sees it from both sides: Her only child is serving life without parole for a crime he committed when he was 18, she said. He’s 43. Before that, her brother was murdered in a shooting. She supports parole for lifers.

“A thousand — a million percent,” she said. “We have to break this judicial system that they call justice when it’s not justice for all of us, but for a few.”

The lawsuit chooses to call life without parole “death by incarceration,” pointing to the fact that Pennsylvania is one of six states in which a life sentence offers no chance at parole. The others are Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine and South Dakota.

“It’s a prosecutor’s net,” Grote said of second-degree murder. “(It) allows them to link the unintended consequences of a criminal act to anybody who participated in the act. (The plaintiffs) participated in a felony. They were guilty of that felony, and during the course of the felony, somebody died.”

No parole options mean those serving the sentence have no chance “to seek redemption by being allowed to return home and give back to their communities and families for past harms they committed,” he said.

The plaintiffs

• Scott, who was given mandatory life without parole in 1974, served as a lookout for a teen who ultimately killed a gas station attendant during a botched robbery, according to the lawsuit.

Her co-defendant was 16 at the time, meaning his life-without-parole sentence was deemed unconstitutional under a 2012 Supreme Court ruling, and he has since been paroled.

During her 46 years in prison, Scott has completed college courses and earned an associate’s degree in sociology, Grote said, and she has formed a group at the state prison in Muncy meant to help incarcerated parents. She has created a newsletter in the same vein.

Scott wrote in the lawsuit that studying for her degree “amazed me so much that I started studying myself and why I came to prison.”

• Reid and Wyatt Evans, 58 and 57, respectively, have been in the state prison system since 1981. They were 19 and 18 when they and another man robbed a Philadelphia man of his wallet, watch and car, according to the lawsuit.

The man died of a heart attack later that day, and the brothers eventually were convicted of second-degree murder under the theory that the robbery caused the heart attack.

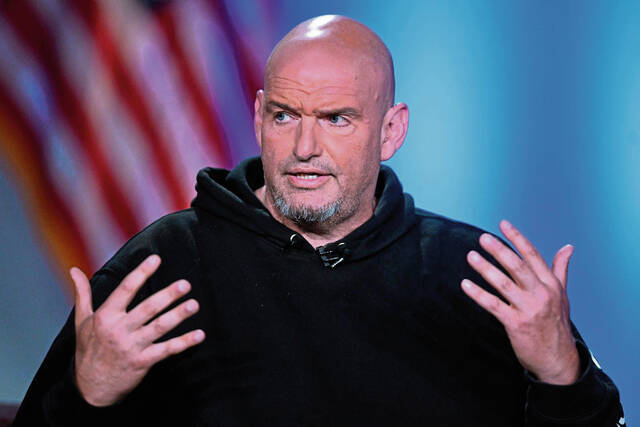

Both men, with the support of Lt. Gov. John Fetterman and the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office, applied for commutations late last year, Grote said. Both were denied.

• Marsha Scaggs, 56, was 23 was she and a co-defendant got into a fight with a man they thought was a police informant, according to the lawsuit. Testimony at the Lawrence County trial indicated that her co-defendant handed Scaggs a gun and told her to shoot the victim. When she didn’t, the co-defendant allegedly took the gun and shot the man himself.

• Normita Jackson, 43, was 19 when she asked a man to her home knowing her co-defendant planned to rob him, according to the lawsuit. The robbery ended with her co-defendant killing the man.

She was convicted just over 22 years ago, on July 2, 1998, in Allegheny County.

Scaggs and Jackson are housed at the state prison in Cambridge Springs, Crawford County. Both have taken treatment classes and other education courses. Jackson is a medical aide in the hospice care unit at the prison. Scaggs organizes fundraisers for the Crawford County branch of Big Brothers and Big Sisters.

Jackson wrote in the lawsuit that she would like to become a productive member of society, hoping to use her story to show adults and children alike that “there is more to life than just drugs, fast money and drinking.”

• Tyreem Rivers, 42, was about six months removed from being considered a juvenile when he snatched a woman’s purse on June 3, 1996, in Philadelphia, court records show. The woman fell and was hospitalized, according to the lawsuit, and died two weeks later from pneumonia.

Rivers now works as a teacher’s aide at a state prison in Luzerne County, where he completed his GED the same year he was convicted, according to the lawsuit. He is a certified paralegal. He wrote that education has changed his life.

“I’ve been 24 years clean of substance abuse, fell completely in love with education, and I’ve reached a point in life where I’m able to help education others through tutoring and advocating for their sobriety,” he wrote.