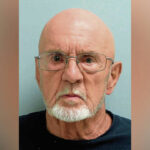

As Terrance Kurhansky’s case made its way through Pennsylvania’s criminal justice system, it became clear to his attorney and the presiding judge that their options were limited, and none of them was ideal.

Kurhansky, 83, was charged in 2019 with attempting to murder his neighbor. Police said he used a handmade rifle to shoot at his neighbor’s home.

Kurhansky believed his neighbor was attacking him with high-frequency radio waves, investigators said. His lawyer said Kurhansky covered his home with tin foil in an attempt to stave off the radio waves before the shooting.

“No one wants Mr. Kurhansky in jail,” said his attorney, James Crosby. “But he also can’t be in Delmont.”

After several years, during which he was moved from Westmoreland County Prison to house arrest at a Coraopolis senior care home, Kurhansky pleaded guilty and was sentenced to eight years in state prison. Still, Judge Tim Krieger was not satisfied with the outcome.

“It’s a sad case from every angle,” Krieger said at a sentencing hearing in August.

Kurhansky’s case is just one example of how mental health issues can create complications at all levels of the criminal justice system, from the police to courts to the facilities that house offenders.

About 2 in 5 people in jail have a history of mental illness — 37% in state and federal prisons and 44% in local jails — according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. That is twice the rate of mental illness within the overall adult population, according to the Arlington, Va.-based organization.

“From a family member’s perspective, when someone has a mental illness and is in the criminal justice system, it’s very difficult to navigate,” said Christine Michaels, CEO of the alliance’s Keystone Pennsylvania chapter. “A lot of people think someone suffering with a mental illness is going to get treatment and medication in the criminal justice system, but that’s not always the case.”

‘A guy at Sheetz’

Circumstances that arise from mental health issues are not always as severe as the Kurhansky case.

Retired District Judge Charles Conway, 72, of Murrysville said people affected by mental health problems can end up in the criminal justice system out of simple frustration.

“You have a guy who keeps coming into Sheetz, let’s say. He’s in there every day and he’s not buying anything, and he’s bothering people,” Conway said. “So the store employees are frustrated. Eventually they call the police, and the police now don’t necessarily know what to do with this guy.”

For Murrysville police Chief Tom Seefeld, it’s a matter of determining what a situation presents.

“A lot of what we deal with is criminal in nature, but we also arrive at scenes to find that people simply need help,” Seefeld said. “Quite honestly, a lot of times people just want to talk to somebody.”

Seefeld’s department occasionally has collaborated with Westmoreland Community Action, which has a mental health crisis hotline and a mobile crisis unit.

“If we recognize that someone is struggling with mental illness, we’ll make contact,” Seefeld said. “We’re not just going to leave someone struggling.”

Michaels said police frequently face a tough choice.

“Police can move someone like that on, or they can arrest them for something minor and put them into the system, which could potentially put them in the county jail for a good amount of time,” she said. “If the county’s medical system can identify someone in jail who is in need, they can be helpful. But if they don’t have connections outside the system to rely on, or if no one knows they have mental health issues or they’re refusing treatment, a person can really deteriorate. Early intervention could help prevent that.”

Sometimes police respond to a situation in which a person has tried to harm themselves or others. In those instances, Seefeld said police undertake what is called a “302” — an involuntary commitment for an emergency mental health evaluation.

Conway said judges can do the same, but he is less confident in its effectiveness.

“I can order somebody to a mental health evaluation and recommend counseling. But does it happen?” Conway said.

“A public defender may say, ‘My guy has mental health issues and should receive an evaluation.’ But that might not be in their best interest because if I agree to that, they’re going to be in jail while we’re looking for beds and trying to schedule an evaluation for months and months,” he added. “In some cases, the wait might be longer than the sentence for the misdemeanor they’re charged with.”

Evaluating defendants

After a mental health evaluation, the waiting isn’t over, Krieger said.

“If someone comes in and requires treatment to restore their mental competency, they go to Torrance State Hospital in Westmoreland County,” Krieger said. “There’s a waitlist for at least two months and longer in some cases.”

A Spotlight PA investigation last March revealed that Pennsylvania laws and policies meant to aid criminal defendants with severe mental health issues often do the opposite. The defendants can be left to languish in jail, exacerbating existing issues as they await competency evaluations and treatment.

Cases in which someone affected by mental health issues is charged with a violent crime create additional complications.

“There are cases where everyone agrees that someone needs to be placed where they can’t harm themselves or others, and we really don’t have a place to put them anymore,” Krieger said. “If someone is accused of a violent crime, a community-based resource is not really going to work.”

In Kurhansky’s case, the home where he had been living was sold by family members.

At a 2021 hearing, Krieger’s frustration was palpable.

“I think anything would be better than him spending his last years in jail because of how the mental health system works here. It’s a choice of cutting him loose with no place to go or keeping him in jail,” Krieger said at the hearing.

Crosby, Kurhansky’s attorney, agreed.

“The first time he was evaluated, they said he wasn’t mentally incompetent, and I can’t understand how the psychiatrist came to that conclusion,” Crosby said. “He was reassessed, but after he was deemed incompetent, there was nowhere to put him. You stay in jail, or you go back to Torrance. And Torrance is not a pleasant place. I’ve sent younger clients to Torrance who begged me to get them back to jail.”

Westmoreland County Common Pleas Judge Scott Mears, who is the court’s administrative judge for mental health cases, said the limited number of beds at Torrance and Norristown state hospitals is a major issue.

“They are generally very successful when they go to Torrance, and the staff there is good at helping to restore competency,” Mears said. “But the problem is the long waiting list to get people to the hospital.”

As of March 1, there were 56 people on the active wait-list for a spot at Torrance and 24 for Norristown in Montgomery County, according to state officials.

“I think if they expanded their availability, that would be a huge benefit,” Mears said. “To me it also makes a lot of sense economically. If you start peeling the onion back, there’s a huge cost involved in health care for the mentally ill.

“If you could triage those cases, you’d save a lot of tax dollars in the long run.”

Limited facilities

Torrance and Norristown state hospitals provide mental health evaluations, offer forensic-level treatment to restore competency and provide a community-based setting for those deemed incompetent. Their 359 combined beds are meant to serve Pennsylvania’s 67 counties.

Torrance officials would not agree to an interview for this story but emailed a statement to TribLive.

Following an evaluation, Torrance staff “will attempt to admit an individual within 15 days of receiving all necessary information/documentation for a particular patient,” the statement said. “The State Hospital forensic units have a maximum capacity of 104 beds at Torrance and 255 beds at Norristown.”

The state has made efforts to expand the availability at state hospitals, adding 100 beds to Norristown in 2017, and plans to add 265 more through new construction, said Brandon Cwalina, spokesman for the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services.

In a January 2023 letter to Gov. Josh Shapiro, the Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association said counties need additional resources to deal with an increase in contact between law enforcement and citizens with mental health issues.

The association recommended more collaboration with state agencies, better integration of behavioral health and substance-use disorder treatment and more assistance on the local level.

“Many of our prosecutors have embraced diversion programs for nonviolent crimes where individuals can receive treatment for mental health and substance use disorder,” the letter reads. “However, these diversion programs only work if there are resources available for treatment.”

In 2022, the state Department of Human Services allocated more than $8 million to Allegheny, Butler, Westmoreland, Delaware, Philadelphia and York counties to implement residential programs and initiatives aimed at reducing the number of defendants waiting for an evaluation or forensic treatment at a state hospital. Cwalina said an additional $4 million was allocated to six southeastern counties.

All of the money is directed to additional mental health programs, which include opening or increasing capacity in regional therapeutic residential facilities for adults coping with mental illness, opening respite care facilities for short-term stays, offering housing vouchers for rehabilitation programs and expanding local mobile crisis response teams.

“Gov. Shapiro’s proposed ’24-’25 budget also provides $1.6 million to support the discharge of 20 eligible individuals from state hospitals who can be served in the community through the Community Hospital Integration Projects Program,” Cwalina said. “It provides additional resources for county programs to develop residential services and community support needed for each person who gets discharged through CHIPP.”

Working to help

Denise Macerelli, behavioral health division director at Westmoreland Casemanagement and Supports Inc. (WCSI), can sympathize with the situations that defendants, police and others in the criminal justice system face.

“When residents are upset or maybe just worried about an individual, a lot of times their only option is to call the police,” Macerelli said. “Then the police come, and if the person is agitated or paranoid, things can escalate really quickly. And that interaction can put someone on a criminal justice path instead of a treatment path.”

WCSI staff do not deal exclusively with defendants affected by mental health issues, but members of its criminal justice liaison program are assigned to district courts. They work with judges and attorneys to help identify people in need of diversion or treatment.

Steve Steinbrugge, the program’s forensic team supervisor, said WCSI regularly hears from judges seeking help.

“A magistrate will call and say, ‘I need to really find out what’s going on so it can guide me in handling this case,’ ” Steinbrugge said. “The program was developed in 2011, and through the years the liaisons have done a phenomenal job building a relationship with our magistrates and with police.”

Program members also work with people on the back end of the criminal justice system.

“We try to build relationships with probation and parole officers and also with resources in the community like private landlords who might work with someone coming out of jail,” program manager Jared Kistler said.

Even with those relationships in place, things do not always run smoothly.

“If a forensic unit in Torrance can’t restore a person’s competency, now what happens?” Macerelli said. “You have to have a place to go. A case manager has to find a place for them to live, a place willing to accept them. Is there a bed open there? The whole backlog in the system and the difficulty with access impacts the ability to move people from the (Torrance) forensic unit when they’re awaiting trial. If they go back to jail while they’re waiting, they may lose their competency, and you’re back where you started.”

Setting aside the criminal justice system, Macerelli said, people with mental health issues still face societal stigma.

“You’re likely to be poorer. You’re likely to be living in a situation where you don’t have a support network,” she said. “You have all of that to begin with, and then you add the criminal justice system on top of that? It just makes solutions very complicated.”

WCSI’s liaison program also uses what they call forensic peer specialists: people who have lived experience with mental illness and can offer their own perspective to a client.

“Peer services are an incredible, powerful tool, and they can be very helpful,” Macerelli said. “But finding peers specialized in forensics can be tough.”

WCSI’s liaisons try to serve as a bridge for clients.

“Sometimes it could just be navigating the system itself,” Steinbrugge said. “Maybe diversion from jail isn’t possible, but we can make some of those strides so that when a person is released, we’re already ahead of the game and working toward them breaking that recidivism cycle.”

No easy answers

Some aspects of the criminal justice system have improved, Kistler said.

“In the last couple years, I’ve seen the relationships improve with magistrates where some of them are noticing, ‘Hey, there might be a mental health issue here,’” he said.

Conway said he’s thankful for the effort WCSI liaisons make but acknowledged they face an uphill climb.

“They can be a blessing when they come in,” he said. “Good ones can spot a mental health issue right away. But you can have a client who no longer has a support network.”

Krieger said he sometimes has to make the best choice from a group of bad options.

“If it’s someone who would otherwise be on home release or parole, what is the best decision when there are mental health issues?” he said. “Incarceration is certainly not always the right choice.”

“When they’re released, there’s a high possibility that they’ll be incarcerated again,” Macerelli said. “And they can’t find a job, they can’t find a place to stay. You add all those things in, and it creates a set of circumstances that don’t necessarily help a person, even if they want to do better.”

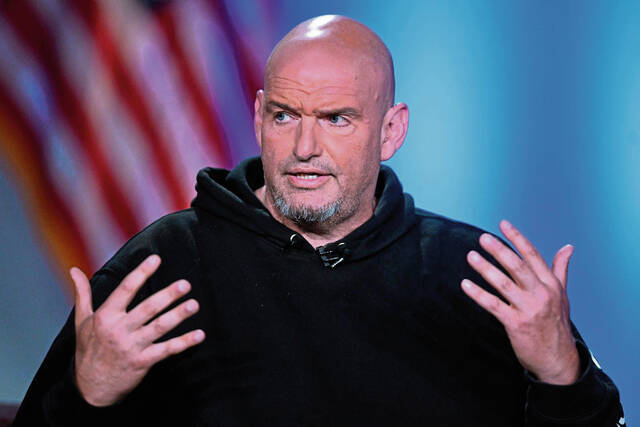

State Sen. Art Haywood, a Democrat who represents parts of Montgomery County and Philadelphia, is vice chair for the Senate’s Health and Human Services Committee. He said incarceration is not going to solve the problem.

“We need diversion of folks with serious mental health needs to treatment, not incarceration,” he said, pointing to a program that has been in place for nearly a quarter-century in Florida.

Miami’s 11th Judicial Circuit Criminal Mental Health Project was established in 2000 to divert people with serious mental illness and substance-abuse disorders away from the criminal justice system and toward community-based treatment.

A 2020 study of the program, published by the Cambridge University Press, determined that it demonstrated “substantial, cost-effective gains in the effort to reverse the criminalization of people with mental illnesses.”

Rather than duplicating existing community services, the project sought to create more effective and efficient links to those services.

In Miami-Dade County, the average daily inmate population went from nearly 7,000 in 2008 to just over 4,200 in 2019, according to the study.

“The Miami model is working, and we should adopt it,” Haywood said.

Crosby said he’s not sure what the answer is.

“It’s expensive to open hospitals,” he said. “There are people who are in need of treatment, but I know politicians can’t really run on a platform of helping mentally ill people who commit crimes.”