Less than a month into a shutdown that forced colleges and universities across the country to transition to online classes, covid-19 is exposing new fractures in higher education.

When students were forced to leave campus months before the end of the spring semester, residential campuses had to come up with millions of dollars in refunds or credits for room and board when they were operating at a break-even level to begin with.

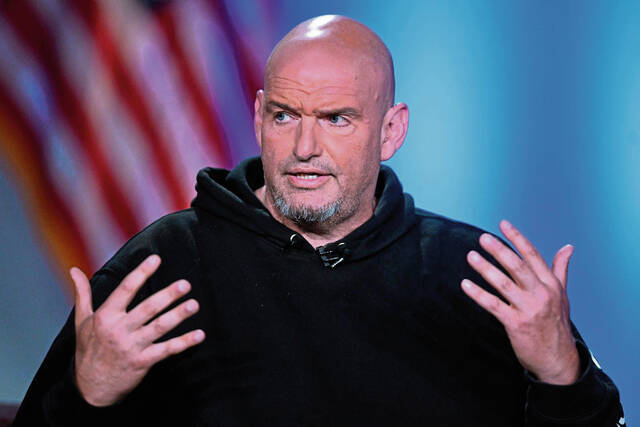

Daniel Greenstein, chancellor of the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, projected the 14 state-owned universities will face a $100 million shortfall this spring due to refunds. The system already is in the midst of a comprehensive reorganization after a decade-long decline in enrollment.

Colleges and universities with students scattered at study-abroad sites around the world scrambled to bring them home as international borders closed.

Across the country, campus tours designed to attract incoming students were canceled just as the college recruitment season began, sparking fears about fall enrollment goals even as soaring unemployment and family hardships raised the specter of dropouts.

Many colleges and universities froze hiring, while others weighed staff furloughs to make ends meet.

And finance officers watched nervously as plunging markets rocked endowment funds and reserves.

Concerns for the colleges and universities, which pump about $640 billion a year into the national economy, prompted financial analysts at Moody’s Investor’s Service to downgrade the financial outlook for higher education from stable to negative.

“Operating performance will tighten across the sector as colleges shift to online education delivery and incur other emergency costs,” analysts predicted.

Experts say any pain colleges and universities experience could ripple across the hundreds of small towns where such institutions are a significant local economic engine.

Barbara Mistick, former president of Wilson College in Chambersburg, is president of the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, which represents more than 1,000 private non-profit institutions. She hears concerns every day from her member institutions.

“We went from a month ago talking about bringing home study-abroad students to shutting down campuses and moving to an online delivery system. Now, questions about layoffs and furloughs are the number one thing in my inbox,” Mistick said.

Locally, that hit home at Saint Vincent College. The small, well-regarded Benedictine college outside Latrobe recently furloughed about three dozen employees across a range of departments, including admissions, alumni affairs and campus ministry.

Calling them “difficult decisions,” college officials declined to say exactly how many employees were cut loose.

“As the situation with the pandemic evolves, the college will continually evaluate campus operations and make the appropriate decisions in the interest of mitigating the impact of the pandemic and ensuring the best use of resources,” Saint Vincent spokesman Jim Berger said in an email.

Mistick said private colleges across the nation are worried about the toll the coronavirus will exact. With unemployment soaring, will families be able to send students back to school this fall?

Even more immediate concerns became apparent as colleges and students attempted to adjust to the new landscape.

At Indiana University of Pennsylvania, student emergencies cropped up quickly among the student body of 10,400 where about 45% of whom are eligible to receive need-based federal Pell grants.

When jobs evaporated, students found themselves struggling to cover rent and buy groceries. When dorms closed, those who relied on computer labs in dorms for internet access suddenly found themselves without the tools needed to access remote classes. Still others returned to homes that lacked Wi-Fi access.

Although the $2.2 trillion federal CARES Act included $6.28 billion to help needy students cover such costs, colleges have yet to see the money, which only became available last week.

“The sudden moves created real hardships,” said Malaika Turner, IUP’s assistant vice president for student affairs.

As of last week, an emergency fund drive raised about $163,000. The university was tapping the fund for emergency grants.

“We reached out to about 600 students. We’ve received a little over 300 applications for aid and awarded about 100. And another 100 or so are in process,” Turner said.

Mildred Garcia is president of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. The organization represents about 400 public colleges. Many of them are public comprehensive universities, like IUP.

Garcia said many of the students at the institutions her organization represents are struggling to meet their most basic needs for food, housing and transportation.

“This highlights the inequities in our systems,” Garcia said. “The bright spot to me is how our institutions are responding. Our institutions are either lending or buying or giving laptops and Wi-Fi hot spots to the most needy. They are reaching out and some of them are even delivering these laptops to their homes.”

As for the future, Garcia said colleges are discussing mergers and tapping technology to share more programs online across institutions.

”People are thinking about that. They’re modeling right now. They don’t know what the impact is going to be,” she said.