Pennsylvania has drawn ire from environmental groups, lobbyists and even a lawsuit from Maryland because of its slow pace to reduce pollution flowing into the Chesapeake Bay. In a state where many residents are not connected to the bay and unaware of the upstream impact on the nation’s largest estuary, efforts to save it have been historically underfunded and overlooked.

Surrounding states point to phosphorus and nitrogen from farms flowing into the Susquehanna River and its tributaries, then running right into the bay.

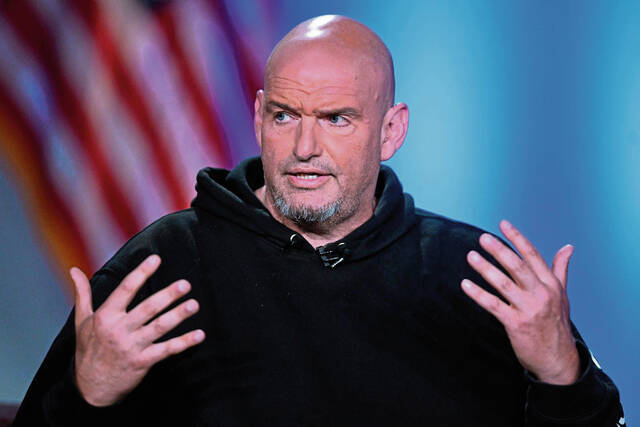

But a new report card, unveiled at a news conference in Harrisburg, with Gov. Josh Shapiro, other state and federal officials, scientists and environmental groups, shows that pointing fingers at Pennsylvania simply isn’t accurate anymore.

A Chesapeake Bay Report Card compiled by the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science gave the Chesapeake Bay its highest grade for health in more than 20 years, a C-plus. The annual report shows that the bay is steadily improving, and the Upper Bay, the area most affected by Pennsylvania’s streams, got the second highest score of any part of the bay.

“We’ve spent a lot of time in Maryland and Virginia pointing fingers and saying it’s Pennsylvania’s fault,” said Bill Dennison with the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. “And it turns out it’s not really true. The data is showing that actions are actually starting to pay off.”

Pennsylvania’s actions center around key partnerships with surrounding states, its farmers and its divided Legislature. A decade ago, communication between the groups was near-impossible.

“Government works best when it works together,” said Jessica Shirley, acting secretary for the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection.

Her sentiment was repeated several times by attendees, which included environmental secretaries from Pennsylvania and Maryland.

Pennsylvania’s Department of Conservation and Natural Resources has worked to plant more than 7,000 acres of buffers adding up to 1.5 million trees along rivers and streams in the state. The Department of Environmental Protection has worked with farmers on conservation efforts, and it’s been working, but it’s been slow, as Michael Mehrazer, the advocacy manager for the environmental group PennFuture said. It could be hard to sustain.

Farms along Chesapeake Bay tributaries

A relatively new focus is the state working with farmers, particularly in agriculture centers like Lancaster County and finding ways to support and incentivize cleaner farming practices.

“I think for a long time farmers were scapegoated for the problems we were seeing in the bay. They were attacked and they were told they had to change the way they things but they were never worked with in a constructive manner,” Shapiro said. “I view our farmers and the agriculture sector as partners in making progress on the bay.”

In 2022, Pennsylvania’s budget included the Clean Streams Fund, dedicated to reducing water pollution in the state. Funding from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) to help farmers use best practices on their farms is running out quickly. The money has to be spent by 2026, and Lancaster County’s allotment already dried up. There’s a waiting list in almost every county for the program.

There’s been no move yet by the legislature to infuse more cash into the program, and Shapiro wouldn’t discuss budget specifics on Tuesday.

“Farmers want to be good stewards and they’re the ones that work on the land,” Mehrazer said. “It can be expensive and difficult to implement best practices [for environmental conservation] and we’re putting a lot of pressure on 1% of the population for something that supports everyone.”

Pennesylvania Agriculture Secretary Russell Redding said that talks for a dedicated funding stream for conservation on farms were in the works for years.

“I think it’s a very clear signal for all those in government that the local led efforts from the county leveraging money, the state putting in money, bringing in and further using the money from the farm bills have given us tremendous momentum,” Redding said. “We have to find alternative funding to keep ACAP funded and sourced in the right way.”

Altogether, the scorecard doesn’t lie. Things have gotten better for the bay, although a C-plus leaves lots of room for improvement.

“We are heartened when we see progress,” Mehrazer said. “We know Pennsylvania has a long way to go and we are not sugar coating that but we have genuinely seen progress. The fact that ACAP has been spent so quickly shows we know the right things to do, we just need to make sure we continue to build political pressure.”

As the Pennsylvania legislature works on a state budget that advocates hope includes more money for the Clean Streams Fund, a different governing body is at work for the Chesapeake Bay.

‘Beyond 2025’ charts bay’s future, despite falling short on goals

Governing the Chesapeake Bay is a daunting task. Six states and Washington D.C. have land or tributaries that border the Chesapeake, each with their own departments of environmental protection, while the EPA provides federal oversight.

The Chesapeake Bay Program engages all stakeholders, in addition to the states, federal and state agencies, nonprofits and academic research institutions. There are a lot of partners, but there is one document that serves as a beacon to guide the program.

For more than a decade, the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement has been the defining document for bay cleanup efforts. It was agreed to by the governors of the watershed states as well as federal environmental program chiefs, but many of the 10 goals and 31 outcomes included in the agreement have 2025 deadlines that have not been met.

The new Beyond 2025 report provides some next steps for the Chesapeake Bay Program.

“The watershed has a strong and hopeful future,” Martha Shimkin, director of the Chesapeake Bay Program Office said. “We are all in and it’s a big and complex effort. It’s a really strong program working across the partnerships.”

The draft’s two main recommendations are that the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Executive Council affirm its continued commitment to meet the goals of the 2014 agreement and that the council draft amendments based on new science and current challenges.

The original goals were challenging, Shimkin said, but what’s been accomplished so far is nothing to sneeze at.

“So much has been done,” Shimkin said. “So many accomplishments have been met and if we didn’t have this program over the past 40 years I can’t imagine the situation we would be in.”

Since 1988, almost 31,000 miles of streams and rivers have reopened to migrating fish, 1.6 million acres of land were protected and the largest oyster habitat restoration in the world took place.

“I want to send that message of a bright future with hard work and accomplishment,” Shimkin said. “It’s a good time to be here and to be leading and it’s a momentous time for us to look at the future of the program and how we can meet new challenges.”