https://development.triblive.com/local/westmoreland/war-on-alcohol-an-experiment-that-was-a-catastrophic-failure/

War on alcohol: An experiment that was a ‘catastrophic failure’

The United States was a battleground before World War I — with armies of people opposed to liquor and saloons lobbying politicians and marching on Washington, D.C., in their mission to outlaw what they considered a scourge on nation’s morality — alcohol.

“Prohibition had been a long time in coming, dating back to colonial times and the early 19th century,” when opponents were concerned that husbands spending hard-earned money on liquor could lead to family poverty and domestic violence, said Jeanine Mazak-Kahne, who teaches American history at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

“A whole lot of people believe it (alcohol) destroys families,” Mazak-Kahne said.

The Anti-Saloon League and Women’s Christian Temperance Union, with the enthusiastic backing from Protestant evangelicals mixed in with a dose of anti-Catholic sentiment, gained more influence in the early 1900s. This highlighted the natural tension between the rural white Protestants and the diverse urban population, Mazak-Kahne said.

“They saw it as a women’s issue. This is one of the key movements to improve family life,” said Laura Tuennerman, a California University of Pennsylvania history professor.

As women fought the right to vote, these groups convinced male legislators to pass various anti-liquor laws in 12 states by 1914.

“They thought they could fix the problem (of drinking) with a law. They saw a need to clean up society,” Tuennerman said. Some pushing Prohibition had a religious fervor and anti-immigrant bent, feeling it was those rapid waves of immigrants flooding the country from Eastern and Southern Europe who brought with them a propensity for drinking and needed to be controlled, Tuennerman said.

They also won the support of powerful industrialists wanting no part of a less-productive, hungover workforce on “Blue Monday,” Mazak-Kahne said.

The opposition to alcohol created unusual political alliances, no stranger than the strong support they received from the Ku Klux Klan, said Mazak-Kahne. The Klan, which hated African-Americans, Catholics and Jews, was a willing partner in the anti-alcohol movement, yet also backed the Suffragette movement to give women the right to vote, she noted. Women finally gained the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

By the time America entered the war in Europe in April 1917, 26 of the country’s 48 states banned the sale of alcohol, spurred on no doubt by the need to feed the troops with the grain that had been devoted to making all that alcohol.

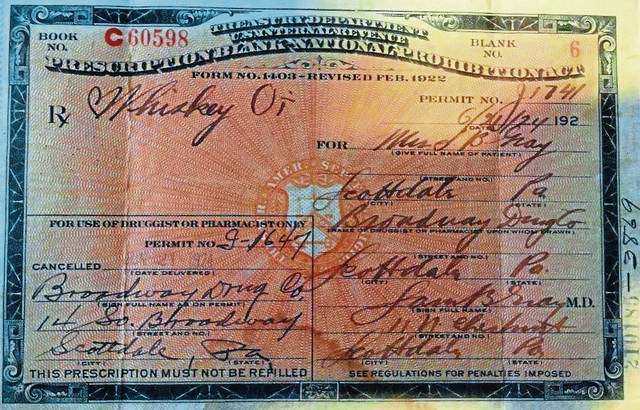

By December 1917, the 18th Amendment was submitted to the states and ratified by January 1919. The amendment lacked the measures to enforce the restrictions, which was remedied with the passage of the Volstead Act, giving the feds the authority to arrest violators. Congress passed it over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto.

The call for repealing the 18th Amendment began as early as 1923 and gained more traction in 1925, as criminals rose to fill the void left by banning alcohol, Mazak-Kahne said. Preventing the production of illegal alcohol, and bootleggers bringing it in across the Canadian border, was near impossible.

With three Republican presidents in the 1920s — Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover — and the Republican Party toeing the Prohibition line, the repeal movement could not gain traction.

It took the election of President Franklin Roosevelt to break the deadlock over Prohibition. By the 1930s, even women’s groups were pushing for the end of Prohibition, Mazak-Kahne said.

Within a few weeks of FDR’s March inauguration, the Democrats pushed through Congress the Beer and Wine Revenue Act, levying a federal tax on the sale of beer with 3.2% alcohol content and wine, thus permitting the first legal sale of alcohol. It raised revenue for the cash-starved federal government struggling through the Great Depression.

“In a sense, Prohibition worked because it reduced alcohol consumption, but it did not end alcohol consumption. Nothing really changes human behavior,” said Tuennerman, the California University of Pennsylvania professor.

That modification of the Volstead Act cleared the path for passage of the 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment.

America’s experiment to control people’s behavior in terms of drinking was a “catastrophic failure,” Tuennerman said. “Most Americans broke the law. It’s the law that made the average American a criminal. Everybody drank a little.”

Prohibition proved, Mazak-Kahne said, “you can’t legislate morality. It never really works.”