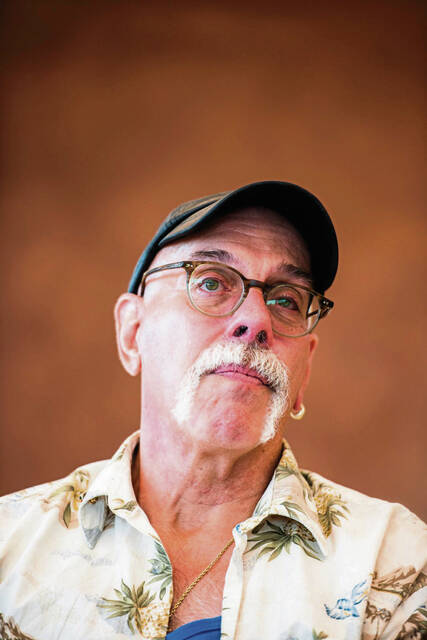

Alex “Mike” Signorini had just methodically returned a drill bit to its case, and he couldn’t wait to text his doctor with the news.

A woodworker and mechanic who managed a tire shop for 38 years, Signorini once spent his days working on cars, jogging and riding his motorcycle. Putting away his tools was routine.

But since he suffered a stroke in May 2021 that left him with limited use of his right arm, old routines had fallen away.

Signorini of Hempfield is one of eight stroke victims taking part in a groundbreaking University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University research study to help patients regain use of their arms through an experimental spinal implant.

In September, Signorini exercised and practiced using the implant at the new UPMC Mercy Pavilion in Pittsburgh. It meant long days, hard work and straining exercises, but he saw improvements.

“The amount of movement and all of the things that I had are so much better,” he said. “When I’m not being stimulated, it’s much better (too).”

Signorini didn’t gain full function in his right arm, and it’s unclear whether the strides he made during the study will persist now that the implant has been removed. But Signorini says he’s seen “quantifiable progress.”

As the fifth patient to participate in the study, Signorini is hopeful his involvement will help others with similar conditions.

“If nothing comes of it for me, hopefully (it will for) someone else,” he said. “I say, ‘Why did I have this stroke?’ I’m here to help someone else. So this is a good way to do that. I hope it’s not just one person — I hope it’s a whole load of them.”

A chance at healing

Heather Rendulic, 34, who lives in Shaler, was the study’s first participant. She experienced a stroke at a young age, suffering five brain bleeds as the result of a rare condition when she was in college in 2011. She was able to relearn how to walk, but her left arm lost much of its function.

In 2021, she went through the same process as Signorini, practicing repeated and functional movements with the help of spinal stimulation. She has retained some of the strength she gained during the trial and can move her wrist in ways that used to be much more difficult.

“I would say I have noticed … an improvement in my function since the trial,” she said. “It’s not as it was when I was in the trial, but it still seems a little bit improved.”

Signorini, 64, is two years removed from his stroke. He remembers falling down the stairs after stumbling out of the bathroom. After initial treatment at Westmoreland Hospital, he was flown to UPMC Presbyterian in Oakland.

He misses jogging, riding his motorcycle and being able to use both arms to hug his girlfriend, Pamela Heller. He recently sold his motorcycle, once his pride and joy.

“All the problem solving was done when running and riding, so I have a little harder time solving some of my problems now than I did before,” he said. “They clear your head, and I miss that.”

He still enjoys woodworking, and he cuts grass, trims trees and helps Heller with her business creating outdoor decorations from vintage glassware.

“I try not to let it stop me from doing as much as I can,” he said. “There isn’t much that I don’t try to do. I’ve never been a person to ask for help.”

He was connected to the study by his daughter, Renatta Signorini, a Tribune-Review reporter.

A groundbreaking study

Dr. Peter Gerszten, a neurosurgeon on the team that performed the surgery on Signorini, compared nerve damage from a stroke to a tree falling on telephone wires next to a house.

“With the stroke, (it’s like) there’s been a big tree that fell on the telephone (wires) from the street to your house,” he said. “Your arms are fine and your body is fine, but you can’t communicate between the outside world, or the brain and the body, because the stroke has interfered with the wires.”

After the surgery, stimulation in the neck — via an implant under the bone but on top of the spinal cord — prompts arm movement through intact sensory nerves.

“Because the motor fibers have been damaged by the stroke, what we can do is we can trick the body — or teach the body — with a certain amount of stimulation to the cervical spinal cord,” Gerszten said.

“We’re boosting the capacity of the spinal cord to receive the information,” said University of Pittsburgh assistant professor Marco Capogrosso, director of the Spinal Cord Stimulation Laboratory, which led the study. He described the stimulation as amplifying what the brain already wants the arm to do.

Rendulic performs consultant work for Reach Neuro, the neurotechnology startup company run by many of the study’s leaders.

“I know stroke affects millions of people a year. This is going to change so many people’s lives all over the world, and that’s just so honoring to be a part of that,” Rendulic said. “It’s really exciting. This is a great time to be alive, and I can’t wait to see how far they go. I know this is going to take off.”

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, nearly 800,000 Americans suffer a stroke each year. Gerszten said he’s been excited by the results of the study and its potential.

“Allegheny County is one of the oldest counties in the U.S.,” he said. “We have an aging population, and just like cancer is increasing in the U.S. as the population ages, stroke is increasing because of the older population.

“With the millions of people in the U.S. projected to have strokes and debilitation from strokes with no treatment, this is the first and only way currently where we will be able to actually improve the function (after) the stroke.”

Restoring function

Signorini kept busy through sessions in the lab at UPMC Mercy Pavilion. His exercises ranged from extending, flexing and moving his arm up and down while being tracked by cameras to navigating a model apartment and completing daily tasks.

“It was always hard to straighten my arm all the way,” Signorini said. “I would have to fight with it. Now, if I’m just standing there — your arms never are straight when you’re standing — and if I say I want to extend it, it feels like a regular arm, whereas before it didn’t do that.”

During a session, Signorini and the lab team chattered back and forth. Signorini let them know when the level of stimulation was uncomfortable, providing data that will be used for calibration. A tangle of wires extended around the room connecting computers, equipment, cameras and Signorini.

In the four weeks that Signorini was participating in the study, the implant was connected to an external generator. The research team hopes to develop a version that would be entirely within the body.

Sometimes the team played music in the background — one day, an Eric Clapton live performance playlist rang out while Signorini flexed his forearm.

“I go home happy that I’ve seen improvements,” Signorini said. “I saw improvements right away.”

The researchers assess strength, dexterity and functional tasks, Capogrosso said. They also calibrate the ideal levels of stimulation so the implant functions best.

“What we’re trying to understand now is, what are the profile of patients who would maximally benefit from this?” he said.

Capogrosso emphasized that this is a pilot study. If the data is encouraging, they’ll be able to approach the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a second round of studies in which patients will be observed with a permanent implant over the course of one or two years.

“When that’s done, this can be deployed as a therapy,” he said. “In the ideal scenario, people would have the implant, undergo a period of rehabilitation like we are doing, and then bring it home and keep using it in their daily life.”

This is an exciting moment in stroke research, he said.

“We are seeing the advent of these neurotechnologies that can really support this,” he said. “This is something completely different. It has never been done.”

The road ahead

Signorini had the implant removed Sept. 28. Afterward, he could still move his arm much higher and lift it straight in front of his body. Some tasks — like lifting his arm to put on deodorant — have become easier. When his arm is relaxed, usually at the end of a day, he practices motions to build his strength.

“I still can’t voluntarily open my hand. I can grab, I can hold, and I think the strength of my hand almost doubled from what it was when I started,” he said. “I gained motion in my wrist that I couldn’t do before.”

He hopes to continue physical therapy and aspires to maintain the improvements he gained.

“If I have gains, maybe I can capitalize on staying better and maybe even expand upon those gains that I’ve got. I want to keep what I get, not give it back,” he said.

For Signorini, the study team has become like family.

“They always try to take care of me. You’re not a number; you are a person. They care. They truly care,” he said.

He misses the routine of the sessions. During the study, he made himself a custom T-shirt with an aspirational target level of his exercises that he hoped to reach, and he wore it frequently.

“It was that way with being a runner,” he said. “Always trying to be better. That’s all I’m trying to do here.”