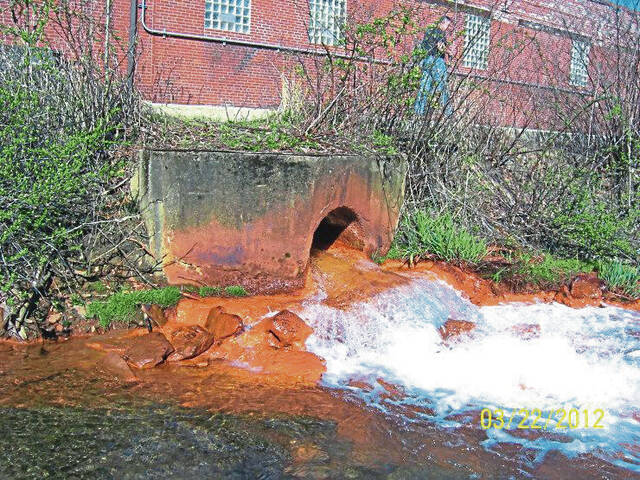

Into Crabtree Creek, every minute of every day, seemingly clear water pours out of a long-abandoned mine, only to turn the rocks over which it flows a solid orange — the color created when the iron sulfide in the mine water is exposed to the air, creating sulfuric acid.

That constant flow of discharge from Crab Tree Mine into the Loyalhanna Creek tributary behind a fire hall in Unity is one of the worst sources of pollution into the waterway, said Josh Penatzer, project manager for the Loyalhanna Watershed Association. The organization seeks to conserve and improve the quality of the 298-square-mile watershed from its source in the western slopes of Laurel Ridge south of Ligonier to where it flows into the Kiskiminetas River at Saltsburg.

“We finished a survey of the watershed and found that 100 miles of the Loyalhanna (watershed) are known areas of concern,” Penatzer said.

Pennsylvania will use the $245 million in federal funds it is to receive annually for 15 years to enhance the state’s Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. The Department of Environmental Protection has yet to determine how the first round of money will be spent.

“Pennsylvania will prioritize the most harmful and dangerous of its 5,000 abandoned mines. The most problematic mines are plotted,” said Jamar Thrasher, a DEP spokesman.

Cleaning up the pollution into Crabtree Creek is the target of an ongoing restoration project that would capture the discharge and pipe it 3 miles to run through a passive mine drainage treatment system with a series of filtering and settling ponds, similar to what is seen behind Saint Vincent College, Penatzer said. The clean water would flow back into Loyalhanna Creek.

The price tag, however, is steep — $15 million.

“These (state) funds are our hope that it (the treatment project) becomes a reality,” Penatzer said.

That’s not the only project on the group’s wish list for a pollution treatment project, Penatzer said.

“There are a bunch of other (watershed) streams we want to clean up,” he said.

Jacobs Creek in the southwestern end of the county also is being impacted by several abandoned mines that are polluting the watershed, said Denise Wilkins, executive director of the Jacobs Creek Watershed Association in Scottdale.

Drainage from abandoned mines has been identified by the state as “major cause of impairment” to Jacobs Creek, as well as tributaries such as Brush Run, Greenlick Run and Shupe Run, Wilkins said of a field assessment DEP performed 20 years ago. Several of those discharges have been or are being monitored, Wilkins said.

“Jacobs Creek is on a pollution waterway list by the federal Environmental Protection Agency,” Wilkins said.

She noted there is a mine drainage discharge below the Bridgeport Sportsmen’s Club that enters into the main branch of Jacobs Creek, and there is evidence of mine drainage at the outlet of the Greenlick Run Reservoir in Greenlick Run. The Brush Run watershed has a discharge near the Bridgeport Dam and a large spoil pile area one mile upstream of Bridgeport.

One solution to treat the discharge has been to create a passive treatment system, Wilkins said, like the one that treats the mine drainage from the Marchand Mine in Lowber. Passive systems move the water through filtering and settling ponds before allowing it to flow into a stream.

“But the problem is the daily maintenance,” removing the orange-colored particles that fall to the bottom of the water as its moves through the treatment system, Wilkins said.

The state providing money to maintain the Sewickley Creek Watershed Association’s three passive mine discharge treatment systems — Lowber, Brinkerton and Wilson Run — would be a big help in removing the orange-colored iron oxide from the settling ponds, said James Pillsbury, a watershed association member and the conservation district’s hydraulic engineer.

The association would like the state to direct some of that money to cleaning up a big discharge from an abandoned mine near the village of Red Onion, between Hunter Road and Keystone Avenue in Hempfield, Pillsbury said.

The Turtle Creek Watershed Association is working on a qualified hydrologic unit plan, a guide to show where there are issues in the 147-square-mile watershed by taking water samples, said Alyssa Davis, association executive director. After that plan is complete, it should make it easier for the organization to access more funding opportunities to clean up abandoned mine discharges, Davis said.

One of the worst of the acid mine discharges is along Tinker’s Run, which borders Irwin and North Huntingdon. The discharge turns Tinker’s Run orange where it meets Brush Creek, which flows into Turtle Creek in Trafford.

Even with the state getting some $245 million annually for the next 15 years, there will not be a quick solution to the mine pollution, Wilkins said.

“It could be a long time between what we propose and what they fund,” Wilkins said.