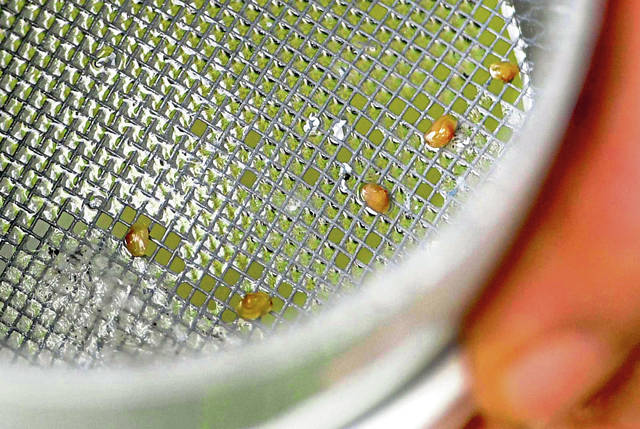

Only a half-grain of rice in size, baby freshwater mussels were deposited in the Kiski River and elsewhere by researchers to better understand and boost the bivalve mollusk’s recovery.

The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy and the U.S. Forest Service installed homemade concrete silos with chambers for the young mussels to live and, hopefully, thrive. Researchers fanned out across Western Pennsylvania last week to place the car-battery-size mussel nurseries into a dozen river and creek bottoms.

Later this year, the researchers will check if the youngsters survived in good quality rivers and streams as well as challenged areas such as the Kiski and other waterways recovering from pollution.

“It’s a field experiment that could result in repopulating areas with mussels in five to 10 years,” said Eric Chapman, director of aquatic science for the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

National mussel expert Wendell Haag, a research fisheries biologist from the U.S. Forest Service, guided Chapman and his crew in handcrafting and installing the mussel silos.

Haag provided the silo’s design — concrete poured into plastic bowls outfitted with PVC pipe to serve as chambers to house the young mussels.

If the effort succeeds, the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission and the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy could introduce tens of thousands of young mussels to waterways like the Kiski, accelerating repopulation and, ultimately, increasing water quality.

This year’s project aims to provide research to the conservancy and others about the factors causing mussel population recovery and decline. In addition to helping with the silos, Haag’s researchers recorded the environmental conditions of area waterways.

Haag’s mussel research project focuses on the causes of declining mussel populations in the Eastern United States. Haag, who lives in Kentucky, has been studying mussels for 35 years. His current research project extends to 13 states.

Visiting a dozen Western Pennsylvania waterways last week, Haag noted area rivers and creeks were “grand and beautiful.”

In addition to the Kiski River, the conservancy and Haag’s team conducted research and placed the mussel silos in Dunkard Creek, Ten Mile Creek, Mahoning River, Beaver River, Shenango River, Sandy Creek, French Creek, Tionesta Creek, Clarion River, Little Mahoning Creek and Mahoning Creek.

Haag’s research could provide a better understanding of how waterways such as the Kiski River are recovering to support mussels.

“How much recovery is necessary for mussels to survive is a big part of our research,” he said. “One of our overarching goals is whether we can identify measurable factors indicative of a stream that can or cannot support mussels.”

That research then helps the fish commission, the conservancy and others who are on the ground trying to conserve and repopulate the mussels in area waterways, he said.

Pollution from coal mines and other sources obliterated mussel populations in the Kiski and other local waterways. Mussels are indicators of good water quality, and they enhance water quality because they are filter feeders.

On average, one mussel can filter 8 gallons of water a day, Chapman said.

Cleaner waters in recent years have brought the mussels back in the Kiski, courtesy of fish from the Allegheny River that serve as hosts for young mussels to catch a ride on before they disperse.

The conservancy discovered eight species in the Kiski last year. It was the first time the species had been documented in at least a century.

Although the survey turned up mussels, there were no large beds of the mollusks found.

A large number of mussel beds can stabilize stream bottoms and increase water quality, Chapman said.

If the young Kiski mussels survive and grow this summer, that opens the door to add thousands more, whether they are youngsters in concrete silos or displaced adults from bridge and construction projects, Chapman said.

About five years ago, the conservancy transplanted about 38,000 mussels in the Clarion River. Researchers salvaged the mollusks from the bottom of the Allegheny River during a bridge project and a pipeline installation. The conservancy will check their status later this year, Chapman said.

The forest service’s current mussel project in Pennsylvania and elsewhere is supported by the BAND Foundation and American Rivers.