Dr. Jerry Rabinowitz believed it was better to be kind than right.

Bernice and Sylvan Simon could have been the poster children for a happy marriage.

Joyce Fienberg doted so much she reminded her son of Mary Poppins.

Rose Mallinger loved to do the chicken dance.

Irv Younger was so kind and loving that a friend once said he hung out with him simply “to bask in Irv’s warmth.”

“It took me 60 years to meet him,” said Judith Kaye, Younger’s girlfriend. “He was the late love of my life. I felt things with him and for him I had never felt before with anyone.

“His death has left me feeling very alone and lost and missing him very much.”

On Tuesday, the government continued to call loved ones of those killed and injured in the Oct. 27, 2018, shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Squirrel Hill as part of the final stage — sentence selection — in the case against Robert Bowers.

Bowers, 50, of Baldwin was found guilty of killing 11 members of the Tree of Life-Or L’Simcha, Dor Hadash and New Light congregations who were worshiping at the synagogue that day.

Killed were Mallinger, 97; Bernice Simon, 84, and Sylvan Simon, 86; brothers David Rosenthal, 54, and Cecil Rosenthal, 59; Dan Stein, 71; Younger, 69; Rabinowitz, 66; Fienberg, 75; Melvin Wax, 87; and Richard Gottfried, 65.

The government is seeking the death penalty, while the defense argues that their client’s mental illness and troubled childhood mean he should be sentenced to life in prison with no chance for release.

The prosecution is expected to wrap up victim-impact testimony Wednesday.

‘I can’t remember a time he wasn’t smiling’

In the 1980s, when doctors were seeing an influx of patients with AIDS — and often were fearful of them — Dr. Jerry Rabinowitz would not only treat them, he hugged them.

It was emblematic of his philosophy as a doctor and a person.

“He wanted to practice medicine the way he thought it should be practiced,” testified his brother-in-law, Daniel Kramer. “He was very present, and he wouldn’t practice any other way.”

Kramer told the jury that even though his sister was married to Rabinowitz, he considered him to be a brother.

He described Rabinowitz’s childhood in Newark, N.J, and spoke proudly of his educational accomplishments — getting full scholarships to college and medical school at the University of Pennsylvania.

Rabinowitz moved to Pittsburgh in 1976, beginning what Kramer called “his decades-long love affair with the city,” and opened his own family practice.

“He was a country doctor — Jerry made house calls, Jerry was the doctor on call for the women’s shelter day or night, weekends,” Kramer said.

He remembered one elderly patient who Rabinowitz knew well.

“After work, Jerry would go over to her house, take her blood pressure, hold her hand and just talk,” Kramer said. “That’s the sort of doctor he was.”

Rabinowitz met Kramer’s sister, Mary, at a singles event to “break” the Yom Kippur fast in 1993. They married in 1997 and lived in Edgewood.

“They’re very silly people,” said Kramer, as prosecutors displayed a photo of the couple on Segways. “They just had a zest for life.”

As a couple, they became active at Dor Hadash, a lay-led congregation active in social issues. Rabinowitz later served as president and head of social activities.

He loved Bible study and planned to read the entire Talmud, the ancient text of Jewish law, after retirement. If he read a page a day — a practice known as “Daf yomi” — it would’ve taken him more than seven years, Kramer said.

Fellow congregants Dan Leger, who was wounded in the attack, and Marty Gaynor are now reading the whole Talmud in Rabinowitz’s honor.

“Dan and Marty are about halfway through,” Kramer said. “They probably have 3½ years to go.”

Kramer also told the jury about a special tradition for Rabinowitz. During the Kaddish, or mourner’s prayer, it is typical that those in mourning stand. Rabinowitz always stood.

Why, someone once asked.

“There are many people who passed away who don’t have people to stand up for them,” said Rabinowitz, according to Kramer. “I’m gonna stand up for them.”

After the synagogue attack, that story about Rabinowitz made its way throughout the Jewish community, Kramer said.

“In synagogues all over the country and all over the world, entire congregations stood for the mourner’s Kaddish, in honor of Jerry.”

Kramer said his brother-in-law also had a saying that he lived by: “It’s better to be kind than to be right.”

The phrase remains on a note card in Mary’s walk-in closet. It sits near a shelf with Rabinowitz’s yarmulkes and prayer shawls, mementos of his Jewish faith.

“We all have taken that to heart,” Kramer said. “We try to think of Jerry and what a virtue kindness was for Jerry.

“This wonderful person’s life was a blessing,” he later added. “And it continues to be a blessing for us.”

As each picture of Rabinowitz was displayed for the jury, Kramer remarked on the smile across his brother-in-law’s face.

“That smile,” Kramer said, with a slight laugh. “I can’t remember a time he wasn’t smiling.

“(His loss), obviously, it’s devastating. My sister wakes up in the house she lived in with Jerry for 30 years — and he’s not there. She comes home from work at night — and he’s not there.”

‘The glue that held us all together’

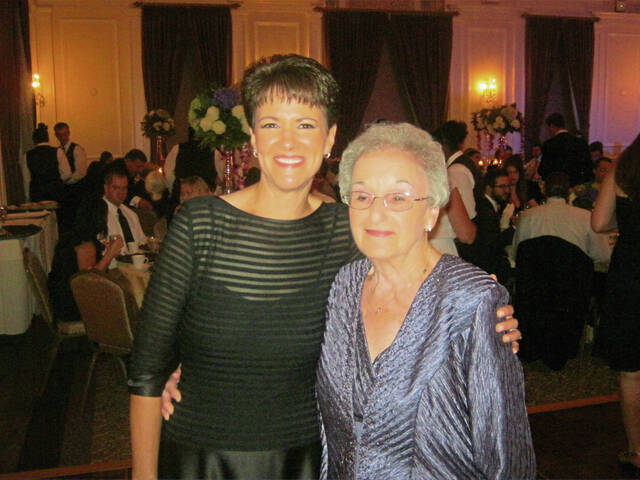

Bernice and Sylvan Simon married in December 1956 — in the Pervin Chapel at Tree of Life.

They also raised their four children in that synagogue.

Michele Weis told the jury that her mom worked as a nurse until she retired in 1999, while her dad worked as an accountant, retiring in 1997.

The couple, whose love, their son said, could serve as a model for others, did everything together.

“They were a remarkable couple,” said Michael Simon. “The way you should treat each other.”

After retirement, they volunteered at a senior center in Turtle Creek, and Bernice also would help teach elementary school students to read.

She loved to cook — Sylvan loved her chocolate cake — and made the best mashed potatoes, Weis said.

“She was my best friend,” she said.

Weis told the jury she spoke with her mom two or three times each day.

Losing both of her parents in such a violent way, Weis said, has been devastating and lonely.

“I’ll never know that love for a parent again,” she said.

Since their deaths, Weis continued, her family no longer celebrates the holidays like before when they gathered at their parents’ home.

“My mother was the glue that held us all together.”

Michael Simon then testified about their father.

Sylvan, who previously served as a paratrooper in the U.S. Army, coached the boys’ little league team and loved watching Pittsburgh sports teams on television.

They had season tickets to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

After retirement, Simon said his parents continued to be philanthropic, donating to a variety of charities even while on a fixed income.

The couple traveled some, and would visit him in California for special family events. Even though he lives across the country, Simon said, they remained close.

“You have a hole in your heart you know will never heal,” he said.

‘Loving kindness’

Joyce Fienberg was a doting mom right out of a children’s book.

“She was kind of like Mary Poppins,” said Anthony Fienberg, 54, who works in insurance and lives in France. “When I think back, she was our world. Our world revolved around her. … She was the guiding principle and, you could say, light when we were growing up.”

Born and raised in Toronto, Joyce married Stephen — a man she met in college, who became a statistics professor — in June 1965. After living in Boston, Chicago and Minneapolis, the couple and their two sons moved to Pittsburgh in 1980.

It was a long time ago, one son said, the year after the Pirates won their last World Series.

The family discovered Tree of Life, a synagogue within walking distance of their Squirrel Hill home. It would grow to become a central part of their lives, and even define them, their sons said.

“Loving kindness” are the words that remind Anthony of his mom.

A cousin was living in Pittsburgh in 2015, while her husband was completing a UPMC residency. Once, Anthony recalled, Joyce bought them tickets to hear the symphony Downtown.

“She didn’t just buy the tickets,” he said with a laugh.

Joyce paid in advance for their parking, drew a map of the route to the parking garage and timed the trip back to the couple’s home so they knew what time to leave to make the show.

“Doting is perhaps the fairest word,” said Howard Fienberg, 49, a lobbyist who lives outside Washington, D.C., in northern Virginia. “She was genetically very detail-oriented and she was going to take care of everything whether you liked it or not.”

Joyce cared intensely for family. She raised two boys while working as a Pitt researcher. Later, she took care of her husband for five years while he battled cancer — a full-time job, her sons said.

Her love overflowed.

She volunteered to care for toddlers while their parents sat in court through the National Council of Jewish Women, which opened a “playroom” in the Allegheny County Courthouse. She also worked with the group Family House to provide a home for families visiting Pittsburgh while a loved one was hospitalized.

Joyce kept in constant contact with her sons; “my mother treated email as long-form prose,” Howard laughed.

And she doted on her grandchildren. Anthony’s kids spent two months every summer in Pittsburgh with Bubbe, a Yiddish word for grandmother.

When news of the shooting reached France, Anthony’s daughter sounded the first alarm.

“Did Bubbe go to shul this morning?” she asked him.

More than four years later, Anthony still choked back tears on the witness stand as he told the story.

“It’s so profound, it’s hard to put words on it,” he said, when asked about the impact of his mother’s death. “It just leaves such a void.”

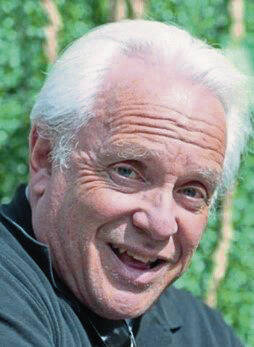

‘We found each other’

Judith Kaye, a psychiatrist, met Irv Younger, who owned a real estate company, when she moved to Pittsburgh around 1992.

She didn’t see him again for 20 years.

On Tuesday, she told the jury she bumped into Younger, whose wife had died about five years earlier, at a Starbucks in 2012.

“We found each other,” she said.

Every time they went out together, Kaye continued, it felt like a first date. As an image of Younger was displayed, Kaye said, “That’s Irv.” And then, almost to herself, “sweet face.”

The Tree of Life synagogue, she said, was a haven for him.

“Irv talked about how kind everyone there was to him after his wife died,” Kaye said.

His faith was important to him, and Younger created his own usher position at the synagogue, greeting congregants and passing out prayer books.

Kaye described Younger, who had two children and fostered several more, as warm and gregarious.

“It was clearly more important to him that he love than be loved,” she said. “It was an unconditional love that he had — unselfish, warm, playful, generous.”

Perhaps his greatest love, Kaye said, was his grandson.

“It was as if his heart was going to explode because he couldn’t contain all the love he had for him,” she said.

As she testified, Kaye told the jury that she and Younger had been invited to a friend’s house the night before the attack, but they didn’t go. Instead, they returned to their respective apartments.

If they had gone, she said, he might have stayed over and slept late the next morning.

He might have skipped Shabbat services.

As she left the witness stand, her pain was almost palpable.

‘She was the core of us’

Rose Mallinger was the center of her family.

Photo after photo displayed for the jury showed the diminutive woman surrounded by family members.

“Everything revolved around her,” said her son, Stanley Mallinger.

“We loved being together as a family, and she was the core of us,” her granddaughter, Amy Mallinger, testified.

Born and raised in Acmetonia, Rose Mallinger’s parents owned a small grocery store in Harmar, where she and her five siblings would help out. It was there, her son said, that she developed her lifelong love of candy.

Rose loved to dance and, in her youth, used to crash weddings to dance at the receptions, her son said.

She and her husband, Morris, married in 1950 and had three children. They moved to Squirrel Hill around 1954 and started attending Tree of Life.

Rose Mallinger was active in the sisterhood there.

After her children grew up and had their own children, Rose proudly accepted the title of “Bubbe.”

“She was the best grandmother,” said Amy Mallinger, the last witness called Tuesday.

She described her childhood and frequent visits to Bubbe’s house — playing games, wiffle ball in the front yard and going to the park.

“If you spent the night, you woke up to blueberry pancakes.”

After Amy returned to Pittsburgh from college, she would see her grandmother two or three times a week, often sitting on the porch, watching the squirrels run across the power lines.

Amy would hold Rose’s hand.

The morning of the attack, Stanley said, he was working on his bicycle in the basement when his sister, Andrea Wedner, arrived at their home to take Rose to services.

“I walked them out the door,” he said. “And that was the last time I saw my mother.”

As news of the shooting unfolded, Stanley said he learned that a woman, who he rightly presumed to be his sister, had been shot and wounded and taken to the hospital.

“‘If Aunt Andrea had gotten out, then Bubbe had gotten out,’” Amy thought to herself.

She and her twin brother spent hours driving to hospitals all over the city trying to find her.

They never did.

Hours later, they learned she had died.

Nearly five years later, Amy said, the family still gathers for events and sits on Rose’s porch.

“She meant everything to us,” Amy said. “She doesn’t get to dance at my wedding.”