At 88, Sister Louise Grundish sits back in her chair, caresses the silver cross dangling from her neck and says point blank she wasn’t always sure that being a nun was the life for her.

There was nothing that could convince her otherwise — not a younger sibling who was a Marist brother, five aunts who were Sisters of Mercy or the cadre of nuns who guided her through Pittsburgh’s former Elizabeth Seton High School, which later merged with South Hills Catholic to form Seton LaSalle Catholic High School.

“At first, I was praying to not be a sister,” she said.

Though she tagged along as a toddler while her dad worked as a reporter covering the state Legislature for two Pittsburgh newspapers, it was her mother’s career as a nurse that she knew would feed her need to care for those unable to care for themselves.

So after high school in 1950, her first stop was Pittsburgh Hospital’s nursing school, which happened to hold its science classes at what was then Seton Hill College in Greensburg.

Once there, Grundish found herself surrounded by the Sisters of Charity — a large, thriving order of women full of energy and devotion to their “charism,” or dedication to loving service in the world.

It was a bit of happenstance that proved life-changing for Grundish.

“My prayers were changed,” she said.

One year later, just shy of her 18th birthday, she entered the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill as a postulate — the first step taken by a woman who enters an order with the goal of becoming a sister.

Times have changed.

Grundish’s order, similar to many others, has lost more than 85% of its sisters since peaking at nearly 900 in the 1960s. Still, with 118 remaining members, it’s faring better than other U.S. orders threatened with extinction.

The number of nuns in the U.S. has plummeted from over 180,000 in 1965 to fewer than 35,000 in 2021, according to statistics from Georgetown University’s Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, the national church retirement office and U.S. Census figures.

Of that number, the average age is 80, according to retirement statistics. Grundish’s order is slightly older, with an average age of 83.

In some areas, orders are fighting to survive by merging with other groups. Some cloistered orders — those dedicated to continuous prayer centered around a convent or monastery — have been forced to close, many unable to meet Vatican requirements that these communities have at least seven members.

In many places, work once done by sisters — from teaching to delivering services to the sick and poor — has been shifted to lay people or eliminated altogether.

Some question how or if the losses can be stemmed.

Others, such as Grundish, say although their numbers are smaller, their work will continue.

Role of the sisters

Although the dwindling number of Catholic priests has gained significant attention nationwide, an even steeper decline among the ranks of nuns and sisters has resulted in the loss of longstanding contributions by these women to the church and society in general, experts indicate.

“The impact of nuns on American Catholicism is big. They staffed and ran parochial schools and colleges and built hospitals and ran orphanages,” said Margaret McGuiness, professor of religion at La Salle University in Philadelphia.

“They were the face of Catholicism. A city might have had four priests and 17 nuns. The nuns were the ones who knew whose parents were out of work, whose parents’ marriages were in trouble. They were the ones that people saw every day.”

The sisters were known for being humble but heroic, said Thomas Rzeznik, associate professor of history at Seton Hall University in New Jersey.

When no one else would treat AIDS patients, the sisters stepped forward, setting an example for other health care workers, he said.

When bishops were reluctant to send priests to fiery civil rights marches in the 1960s, it was “sisters who went to places like Selma and were photographed in their habits and made the front pages of newspapers,” Rzeznik said.

“They didn’t draw attention to their work. The phrase often repeated is to ‘say little but do much.’ The institutions (that they founded) spoke for them … places like St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York and Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh,” he added. “People went to places like Mercy because they would be treated with dignity and wouldn’t be stigmatized because of their beliefs or poverty.”

The Sisters of Mercy founded Pittsburgh’s Mercy Hospital 175 years ago but handed the hospital over to UPMC in 2008, using the proceeds to fund a foundation providing grants to underserved communities.

In Western Pennsylvania, nuns were both health care and education trailblazers.

What is now Carlow University was founded by the Sisters of Mercy in 1929. Today, one sister is on staff. Sister Sheila Carney, 77, is tasked with keeping the values of the order alive at the school.

Likewise, at Seton Hill, founded as a college 104 years ago by the Sisters of Charity, only three sisters are on staff.

“When I was a student here in the 1970s, there was a sister in every room,” said Sister Susan Yochum, the school’s provost.

At its peak in 1965, the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill had a broad reach, staffing 15 high schools, 47 elementary schools and five kindergartens. They manned a school for the deaf — the DePaul School in Pittsburgh — a nursery school, a social service center, three general hospitals — the now-defunct Jeannette District Memorial Hospital, Pittsburgh Hospital and Providence Hospital in Beaver Falls — a school of nursing, a foundling home in Pittsburgh and a foreign mission in South Korea.

Today, although some of those programs may be gone, Yochum said the good work of her order continues. She pointed to the college’s enduring liberal arts mission and the fact a college of osteopathic medicine, a doctoral program in physical therapy and a nursing program have been launched to meet rising demands in those fields.

And the seed the sisters planted in South Korea has grown into a separate branch of the order, boasting about 200 sisters there.

When did the slide begin?

Church leaders say forces within the church, as well as shifting cultural winds that reshaped American society during the last half-century, have buffeted religious orders.

“People rarely left religious life before the 1960s,” La Salle’s McGuiness said. “The decline really started between 1963 and 1965. They left for a lot of reasons. The world was changing. And once a couple left, then everyone (felt they could) leave.”

Many point to the Second Vatican Council, which ended in 1965, as a turning point for nuns everywhere.

Vatican II, as it is known, called for radical transformation among the “women religious,” as sisters and nuns are known within the church. It urged orders to move from rigid structures to more flexible groups that encouraged individual freedom and “intense self-examination and renewal.”

Experts say sisters did what the Vatican asked and re-evaluated their lives, only to question whether the paths they chose were best for them.

For the first time in their religious lives, sisters were permitted to dress in street clothes rather than traditional habits. They could choose their own careers, live on their own and choose when to pray.

Some said the changes were too fast. Others felt the changes robbed them of their special standing in the church, a standing they attained the day they pledged their lives to God and took vows of poverty, obedience and chastity.

Some church males believed the sisters were given too much freedom to be socially and politically active, creating tensions that festered for years.

But many experts say the tide shifted because of expanding opportunities that came with the women’s rights movement of the late 1960s and 1970s.

All along, sisters “were the pioneers for women’s education,” even long before the women’s movement took hold, McGuiness said.

“For some, particularly women from poor immigrant families, becoming a sister was the only path to higher education,” she said. “These women were getting Ph.D.s long before women were getting Ph.D.s in great numbers.”

The women’s rights movement gave these same women other options to achieve success and fulfillment. Some who might have become nuns chose other paths. Some who already were nuns decided to quit to pursue interests available to them outside the sisterhood.

Suddenly, these women realized they could have it all — educations, meaningful careers and families — and still make a difference in the world, said Maureen O’Brien, an associate professor of theology and director of pastoral ministry at Duquesne University.

Joining later in life

In the 1950s and 1960s, most women such as Grundish joined orders while in their late teens.

Today, most women entering U.S. religious orders — only about 200 each year — are anywhere from 28 to 49 and already well-educated, said Sister Mindy Welding, board chair for the National Religious Vocation Conference and delegate for Religious and secretariat for Clergy and Consecrated Life in the Diocese of Pittsburgh.

Some orders wonder when, or if, a new member will ever be added.

At the Sisters of St. Joseph in Baden, Beaver County, a new sister has not joined in 25 years, according to congregational moderator Sister Sharon Costello. The average age of the group’s 116 members is 78, Costello said.

A check of Pennsylvania orders turned up two women in the process of joining religious orders.

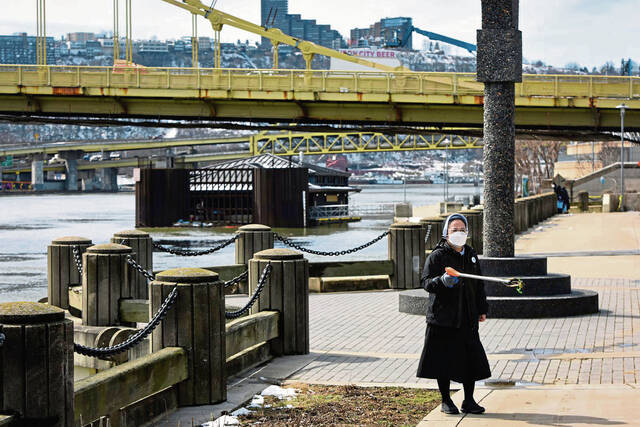

Hyeon Lee, 49, is scheduled to profess her final vows at Seton Hill shortly after Easter. She is in seclusion, contemplating those vows.

The other woman, Elizabeth McGill, is typical of women taking this step today.

A former college soccer player and coach, McGill, 37, grew up in an active Catholic family that often hosted nuns and priests. She earned a doctoral degree, landed a job as an administrator at a medical school and purchased a home by the time she decided she could no longer ignore a call to religious life.

“I took that moment to take a good look at my life and said, ‘How do I want to live my life and how do I want to make my mark here on earth,’ ” McGill recalled.

She is working as director of student services at Marywood University in Scranton, living with three Immaculate Heart of Mary sisters and midway into the yearslong process of preparing to profess final vows that will make her a sister.

Filling the void

Most experts believe there is little that can be done to bring religious orders back to the peak levels of the 1950s, but both the sisters and church leaders say they must continue the work the sisters have supported for decades.

“Throughout the course of our 179-year history, the Diocese of Pittsburgh has been generously blessed by the presence of a number of religious communities of women who, in fact, have helped our diocese become what it is today,” Bishop David Zubik said.

While their number has declined, Zubik said, their work continues “as testimony to their dedication to the work of Jesus” and an example for those the church hopes will fill the breach.

In many cases, filling that breach means training lay people to carry on the work and the spiritual mission once handled by the sisters. In some areas, social service agencies have assumed the work.

“The women religious … were the backbone of the people who brought forth our Catholic education systems and sustained them and so many of our social outreach programs,” said Bishop Larry J. Kulick of the Diocese of Greensburg.

Kulick said that in the Catholic schools, “they would teach during the school year and then they go out into the rural parishes, especially in Indiana and Armstrong counties, where they would provide religious education for children who were not in Catholic school.”

That kind of outreach cannot be lost, Kulick said.

To address the issue, the diocese has been inviting lay people to become certified in “pastoral ministry” through a two-year program offered through Seton Hill. To date, about 150 people have graduated and now work performing many of the duties once done by the sisters.

Work will go on

Grundish looks back on her life as a sister, nurse, nurse educator and most recently as a professional archivist with her order with satisfaction.

Despite her initial doubts, becoming a sister is a life she has loved, and she is certain that mission will continue long after she is gone.

All she has to do is look around her.

“I think God has his own designs in this and the few younger people we have, they’re very alive, very interested,” she said. “There is a whole new work to be done.”