Story by DEB ERDLEY

Dec. 17, 2023

Four days after Christmas 2020, Hannah Moore felt horror like no other when she awoke to find her 2-month-old daughter’s cold, lifeless body nestled next to her in bed, inches away from her other two children.

Traces of blood trickled from Avery Davis’ mouth and nose as Moore frantically dialed 911. Her father-in-law, who was staying with the family in their home just north of Kittanning, desperately performed CPR on the ashen child.

• Experts tell firsthand stories of children harmed by addicted parents

• As substance abuse rises, need for additional programs comes into focus, experts say

In the days that followed, Moore learned from the Armstrong County Coroner’s Office that Avery’s death likely was the result of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. That changed two weeks later when authorities appeared on Moore’s doorstep with a toxicology report. It showed amphetamine, a prescription stimulant, and methamphetamine, a highly addictive stimulant, in Avery’s body.

State police charged Moore, 32, with criminal homicide. They alleged Avery died by drinking breast milk poisoned as a result of her mother’s illicit drug use.

Avery became one of the tiniest casualties in a surge of Pennsylvania children sickened or dying as a result of their parents’ drug abuse, an alarming trend borne out in a TribLive analysis of 845 detailed reports of child deaths and “near deaths” attributed to abuse or neglect from 2018 to 2022. The reports, filed by county child welfare agencies, are posted on the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services website quarterly.

TribLive’s examination showed:

• Drugs were a factor in nearly 1 of 4 incidents during that period, including 70 deaths and 170 “near deaths,” although experts say those reported numbers are woefully low because of flaws in how and when the statistics are recorded.

• Most drug-related deaths reported during that period — 56 of 70 — involved infants and toddlers from 6 days to 2 years old.

• Drug-related deaths among children outnumbered reports of deaths attributed to gun violence by 2 to 1.

• In more than half of the deaths and close calls, the reports indicated someone previously alerted a child welfare agency that a child was in danger.

• In Avery’s case, a regional review by county and state officials conducted after her death showed there were four alerts filed before her death, including one by UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh staff who found methamphetamine in the baby’s system during her 3-week check-up.

When pressed for answers about TribLive’s findings, child welfare officials said chronic staffing shortages, a dramatic increase in drug abuse by parents and other caregivers, and fallout from mandatory reporting laws enacted after the Jerry Sandusky sexual assault scandal have made it difficult to keep up with complaints.

Day in and day out, Dr. Rachel Berger, a research pediatrician and clinician at UPMC Children’s, sees an alarming increase in the number of children — some only days old — showing up in her emergency room with illegal drugs in their systems.

In the first 100 days of this year, the hospital treated 57 overdose victims under age 12, she said. It has become so common that emergency room workers at Children’s and other local hospitals routinely give Narcan — a drug reversing the effects of opiates on the brain and restoring breathing — to any child who arrives in an altered state, Berger said.

Although numbers in official state reports show an uptick in drug deaths and close calls among children, she said, those statistics are “a major underestimate” of the actual severity of the problem because of how information is gathered.

For instance, if a child is revived by first responders with Narcan and is alert upon arrival in the emergency room — as often is the case — that child is not counted in official reports, Berger said.

Also, because Narcan is widely available, caregivers may administer it to children who have overdosed but never report it to authorities.

There often are long lags — sometimes up to a year — in when the information is reported, she said.

Drug overdoses kill an estimated 100,000 people a year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But the youngest victims largely have been ignored, experts said.

“No one has documented in any real way that this is not just a toddler here or a toddler there. There is a dramatic impact that has been so far off the radar in this commonwealth,” said Cathleen Palm, founder of the Center for Children’s Justice, a nonprofit focused on children’s welfare in Pennsylvania.

It’s time for officials to pay attention to the fact children are dying at a frightening rate at the hands of drug-abusing parents, she said.

“Everywhere you turn there are these red lights flashing: The baby’s not OK; the mom’s not OK. That’s why it’s all so frustrating. Most of these are preventable deaths,” Palm said.

It’s a crisis illustrated in a sampling of recent incidents across Western Pennsylvania:

• A stamp bag of fentanyl was found in the throat of 7-month-old Zhuri Bogle, who was pronounced dead in her Penn Hills home in January.

Police charged the child’s grandmother and her boyfriend, who were babysitting on the night Zhuri died. They are awaiting trial.

• Two-year-old Robert Craft was found unresponsive by police in a Munhall apartment littered with thousands of bags of heroin along with needles and other drug paraphernalia, reports show. Robert died hours later at Children’s Hospital. Police said two other children in the home, ages 4 and 7, were tested. The 4-year-old, who police said became “lethargic and incoherent,” tested positive for fentanyl but survived. The parents were charged in the 2022 case and are awaiting trial.

• Earlier this year, 4-month-old Naoki Hines died after his mother found him unresponsive in their Carrick home. Fentanyl was found in his system, records indicate. Investigators said they found a stamp bag of fentanyl in the house. The mother, Katie Grimes, 33, has been charged in connection with the baby’s death and is scheduled to stand trial.

TribLive’s investigation found other children who didn’t die from ingesting drugs but perished because of their parents’ actions while under the influence of drugs.

On Oct. 4, a 32-year-old Lancaster County woman was found unconscious in her bedroom after injecting methamphetamine, leaving her 3-month-old daughter to die locked in a hot car outside her home. The woman, who previously lost custody of two older children, was charged with third-degree murder, involuntary manslaughter and endangering the welfare of children.

In another case, a Franklin County woman was charged with involuntary manslaughter after police said she took drugs and then fell asleep on top of her 6-day-old son, suffocating him. The woman told police she took a drug called “scramble,” a mixture of heroin and fentanyl, before feeding the baby his bottle. She told police she sat cross-legged with the baby on her lap but eventually fell forward onto him while holding the bottle in his mouth.

Still other children have died in the midst of drug operations.

A 5-year-old girl died of fentanyl exposure in a Johnstown drug house in October 2022 and a Philadelphia toddler was shot and later died after his father used him as a human shield during a drug deal that went bad.

One of the biggest hurdles to dealing with the problem is a child welfare system that was created to deal with abuse but ill-equipped to deal with the epidemic of addiction, Palm said.

“Federal law and state law are very clear that a baby being born exposed to drugs is not child abuse,” Palm said. “The challenge we have as a society is not the concept of recognizing that families are under stress, particularly if you have an active substance abuse and infant in your home. That is a real stress. The problem is we as a society have created an infrastructure that is only to deal with child abuse.

“If we had a system where a nurse would to come to the home the first six weeks or first six months, no one would hesitate to make that call.”

State Attorney General Michelle Henry said she believes it will take a collaborative effort by law enforcement, health care providers, social services, community leaders and educators to wrestle the problem to the ground.

Palm and other child advocates have pushed to use money in a state trust fund from settlements with opioid manufacturers, distributors and pharmacy chains to protect children by creating programs that would guide the addicts toward sobriety while ensuring their children are safe.

Those are changes that might have saved Avery Davis, experts said.

For Hannah Moore, the gut-wrenching grief and guilt of that fateful December day when her daughter took her last breath are evident as she spoke quietly and carefully, but candidly, about the addiction that killed Avery.

“I deserve everything I’ve gotten. It made me look into myself and see what I wanted,” Moore said during an interview at a restaurant near her Kittanning home.

She is dressed casually, sporting athletic shoes, a long-sleeved T-shirt and jeans. Her hair is up in a ponytail. Nearly three years after Avery’s death, she still can’t talk about the knock on her door that January day when she learned she was a suspect in the death.

“I’ve tried to block that day out,” she said, wincing.

Because she was pregnant with her fourth child when she pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter, she was sent to the State Correctional Institution at Cambridge Springs, a women’s prison in Crawford County 100 miles away from her children, instead of the Armstrong County Jail.

After spending the better part of a year at Cambridge Springs, where she gave birth to a son, she moved to a community corrections center in Pittsburgh. She is participating in an 11-month intensive drug treatment program aimed at taming her addiction to Adderall and methamphetamines. She hopes to complete the program in February.

While she does, she is living with her parents, commuting to her treatment and dreaming of the day she can be reunited with her children, who are living nearby with family members.

“I never wanted to leave my kids,” Moore said. “I don’t have anything to blame it on. I had a good home. My parents, they’re still together. It wasn’t a broken home or anything like that. My husband — we’re not married, but we’ve been together for more than 11 years, and he is the father of all my 4 children — has stood by me.

“You hear these stories about people with terrible lives, but I don’t have anything to blame it on. … If I could change (my addiction), I would.”

She said the drugs helped get her through busy days after the birth of her second child or to have more fun if she had a “night out,” court records indicate.

Virtually no one knew about her drug use.

“The first time I tried Adderall (a prescription stimulant), I just loved it. I was able to do so much,” she said. “Then I lost sight of how I was able to do it without it. Now I can’t imagine doing that. My days are a struggle, but everyone has their struggles.

“This could happen to anyone.”

!function(e,n,i,s){var d=”InfogramEmbeds”;var o=e.getElementsByTagName(n)[0];if(window[d]&&window[d].initialized)window[d].process&&window[d].process();else if(!e.getElementById(i)){var r=e.createElement(n);r.async=1,r.id=i,r.src=s,o.parentNode.insertBefore(r,o)}}(document,”script”,”infogram-async”,”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”);

A recent study by researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia found overdose deaths among children quietly have been piling up across the U.S. for more than a decade.

The study published in the April edition of Pediatrics, a publication of the American Academy of Pediatrics, found the explosion has been fueled in recent years by ubiquitous, highly lethal fentanyl.

The CDC cites the drug as the leading cause of overdose deaths in the nation among people of all ages, with 73,654 deaths in 2022. That’s more than double the number of deaths reported in 2019.

Fentanyl, a highly toxic synthetic opioid once reserved as a painkiller to provide comfort to patients with terminal illnesses, now is found in nearly all street drugs. It’s less costly to manufacture than heroin, and experts say it can be anywhere from 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

It’s a deadly landmine for unsuspecting children who come into contact with it.

The Philadelphia researchers examined records from 40 states and found opioids accounted for about half of all 731 poisoning deaths involving children 5 and younger between 2005 and 2018. That’s up from 24% in 2005.

More than 40% of the deaths involved children less than 1 year old. Child protective cases had been opened in just 13% of those situations prior to the deaths, the study showed.

Pediatricians told TribLive there is growing concern in the medical community about the escalation of drug-related dangers to children.

“The prevalence of drug use and dangerous drugs is so common. The whole landscape of drug use has changed,” Berger said. “This is insane. Our child welfare system is literally collapsing under the drug abuse we see. We weren’t set up to deal with this.”

Child welfare officials say it is a daily struggle to handle the volume of reports about potentially dangerous situations involving children.

Bryon Bornman, executive director of the Pennsylvania Children and Youth Administrators Association, said his members, like employers in the private sector, are facing crippling staff vacancies.

In Pennsylvania, where child welfare services are administered at the county level, agencies were taxed to handle a dramatic uptick in reports of suspected abuse and neglect after state lawmakers expanded the ranks of those required to report possible sexual assaults following the Jerry Sandusky scandal at Penn State University in 2012. The explosion of drug abuse and recent staffing shortages at child welfare agencies exacerbated that challenge.

“In the best of times we average about 15% vacancy rates among caseworkers. This year it’s been up to about 35%,” Bornman said.

In some counties, the vacancy rate is 60% to 70%, he added.

The overwhelming demands of the job, coupled with significant educational requirements and what some perceive as pay not consistent with employers’ expectations, have played into shortages nationwide, experts said.

The growth of multigenerational drug abuse in which parents, their siblings and sometimes grandparents have drug problems has made it even more challenging to find family members who can assume guardianship when parental drug abuse threatens small children, Bornman said.

“Substance abuse is a disease and an aggressive disease,” Bornman said. “You wouldn’t take kids away from someone having cancer, but maybe you would if you have a parent getting chemotherapy and can’t care for kids. There needs to be a floor of safety for kids. There needs to be a minimum amount of safety assured for the kids.”

In the case of Avery Davis, a heavily redacted regional review conducted after the child’s death revealed Armstrong County child welfare officials had followed up in some manner on four separate complaints prior to her death. No criminal charges were filed, and the child remained in the home even after methamphetamine showed up in her urine during a checkup.

The Armstrong County child welfare office did not return messages seeking comment.

Avery’s mother admits to snorting methamphetamine now and then after Avery’s birth, but she said she was careful to “pump and dump” her breast milk, hoping to protect her baby. Because of that, she questioned the validity of the tests performed on Avery at Children’s Hospital but submitted to testing herself, which records revealed was negative. She said she heard nothing else from child welfare officials about the matter.

Amid the explosion of drug abuse, some child welfare agencies have changed their protocols.

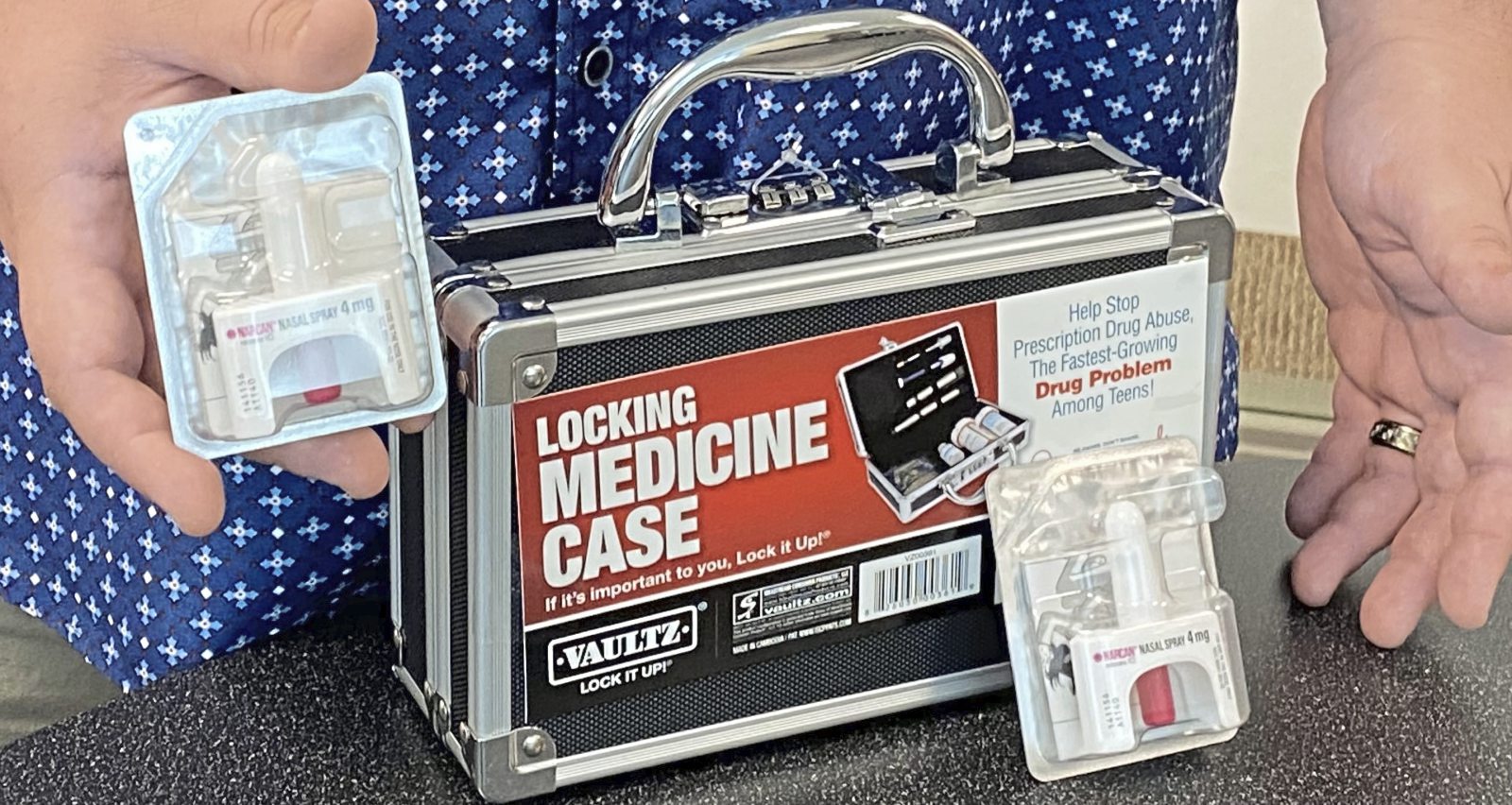

Shara Saveikis, director of the Westmoreland County Children’s Bureau, said the problem is so widespread that caseworkers routinely distribute Narcan and boxes to lock up medication to families with known substance abuse issues — all in an effort to protect children.

Attorney David Shrager, who defended Moore, said such cases illustrate the lethal hold drug addiction can exert on people who otherwise would guard the safety of their children with their own lives.

“It talks about how the brain is fundamentally rewired (by drugs) and that it would take a good and conscientious human being and make them neglect their children,” he said. “It erases free will as we understand it, and a lot of people don’t get it.”

Reporter Deb Erdley spent six months analyzing 845 documents detailing the deaths and near-deaths of children under the age of 18 across the state from 2018 to 2022.

The documents reviewed by TribLive contained information reported by Pennsylvania child welfare offices under a federal mandate. They had names redacted to protect the privacy of the families but contained details that included the dates when children died or nearly died, their ages and gender, and the county of residence. The documents also noted whether criminal proceedings were initiated at the time the reports were filed, the relationship of those responsible for the children and a brief account of how the death or near-death occurred.

Erdley found that reports of child deaths attributed to abuse or neglect across Pennsylvania have more than doubled over the last decade, with records from the most recent five-year period indicating drug-related fatalities fueled a significant portion of that increase.

Correction: The county-by-county graphic above showing Pennsylvania children’s drug-related deaths and near deaths contained incorrect information. The graphic has since been corrected.

Deb Erdley is a Tribune-Review staff writer. You can contact Deb at derdley@triblive.com or via Twitter @deberdley_trib.