Seated at a table of nonscientists, Kaigham “Ken” Gabriel explained how an ordinary-looking construction site in Hazelwood just might propel Pittsburgh to the forefront of reducing medical costs through gene therapy manufacturing.

To make his point, the newly hired CEO of the University of Pittsburgh’s BioForge initiative pulled from his pocket a cellphone — a now-ubiquitous device that decades ago cost thousands of dollars.

“I’m old enough to remember when the only people who could afford these were Wall Street investors, and they were the size of two bricks,” Gabriel said of those early phones. “A lot of people — hundreds and thousands of people — thought deliberately about how to make these things smaller, more affordable and in greater numbers.”

He added: “It’s the same for biology.”

That’s why Gabriel is out in the community promoting what he sees as the promise of Pitt BioForge and its advanced manufacturing capabilities.

In a recent meeting with TribLive editors and reporters, Gabriel said a fundamental shift is occurring in how medicines and therapeutics are delivered to people. Innovation is moving from an era of chemicals and drugs, he said, toward gene and cell therapies for conditions such as cancer, blindness and degenerative neurological diseases.

These cell-altering therapies yield “amazing results,” Gabriel said.

But their astronomical prices often put them out of reach.

For example, Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, though in existence for a decade, costs half a million dollars for a single therapy, he said. Therapies for degenerative neurological diseases in children run $3 million a pop.

“You’re not gonna get very far when it costs that much,” he said.

That’s where Pitt leaders believe their most ambitious research venture in recent years could be a game changer.

“BioForge is going to focus on the innovations and breakthroughs that are needed to manufacture precision biological medicines, so we can speed their delivery, use and impact,” said Gabriel, an internationally known engineering and life sciences entrepreneur.

BioForge won’t be another medical research center in the traditional sense, he said. Pitt already has $658 million in funded research from the National Institutes of Health, sixth largest of any institution in the nation.

Instead, BioForge will bring those inventions to scale by making them less costly and more reliable, said Gabriel, who is also director of its Advanced Biomanufacturing Institute.

“I firmly believe as an engineer, but also as someone who knows how to talk to life scientists and biologists, that there is no law of physics that says these treatments should cost half a million dollars or $3 million,” he said.

Many variables influence what patients pay for life-changing treatments, from raw material costs to insurance coverage to profit pursuit.

“I can’t control those things,” Gabriel said.

But if the issue involves manufacturing, Gabriel says BioForge could be the difference, cutting costs in some cases potentially by a factor of 10.

Where it all happens

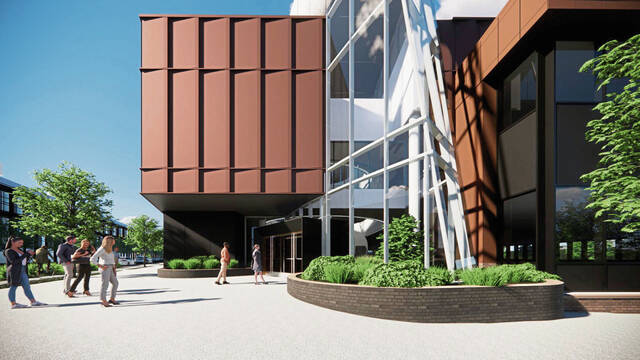

Set to rise in a former brownfield and old mill site in Hazelwood Green, BioForge is a massive undertaking that will tap into Pitt and UPMC’s vast biomedical research and clinical expertise.

It is already benefiting from a Richard King Mellon Foundation grant of $100 million, the largest single-project grant in the foundation’s 75 years.

Campus and government leaders have said BioForge, an LLC subsidiary, has the potential to draw to this region an entirely new economic sector built on Pittsburgh’s existing health sciences expertise.

Former Gov. Tom Wolf said as much in August 2022 during a trip to Pittsburgh marking an announcement that ElevateBio, a Cambridge, Mass.-based cell and gene therapy firm, had entered a 30-year partnership with BioForge to accelerate the development of highly innovative cell and gene therapies.

“Pittsburgh is already great as a leader in manufacturing, and today the city is transforming itself once again as a manufacturing leader but also as an innovation leader,” Wolf said.

“Gene therapy is able to create spectacular treatments and cures for cancer, for a variety of chronic diseases and, I believe, very soon even for Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease,” he added.

BioForge has major strategic implications for a university whose medical history includes such milestones as discovery of a polio vaccine and organ transplantation breakthroughs.

Pitt’s six health sciences schools have enormous research and development capabilities and are affiliated with a sprawling hospital system serving 5 million people, said Dr. Anantha Shekhar, Pitt senior vice chancellor for health sciences and dean of its school of medicine.

“What we lack here is the ability to take our research into patients and into rapid product development and patient testing,” he told TribLive on Tuesday.

That became clear during the covid-19 pandemic, he said, as Pitt developed vaccine ideas. As early as February 2020, Pitt came up with a neutralizing antibody for covid-19 in its research labs.

“But we could never get those antibodies to even be manufactured in settings high-quality enough to test in humans before the summer of 2023, because the manufacturing capacity was all locked up by Pfizer and Eli Lilly and others,” Shekhar said.

BioForge stands to give Pitt a manufacturing capability that only those commercial labs have, a boon to Pitt scientists and researchers at other top universities, Shekhar said.

“If my discovery can become a treatment in two years in Pittsburgh, why would I want to stay in Stanford and struggle for 10 years to get it to market?” he said.

There would be financial advantages, too. “Let’s imagine we develop the next best treatment for congestive heart disease or the next best treatment for breast cancer or colon cancer,” he said. “We would be looking at — even if we get 20% of that — we’d be looking at annually several hundred million dollars.”

In June, Pitt trustees approved $120 million to construct the core and shell of the planned cell and gene therapy manufacturing center at BioForge.

The building is expected to be completed in summer 2026, and ElevateBio is expected to begin work in mid-2027.

Pitt announced Gabriel’s hiring in January. He has built a decades-long career as an innovator working in government, academia and the commercial arena.

He is a former CEO of Draper, an MIT spin-off engineering company, and has served as deputy and acting director of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Gabriel is a former tenured professor in the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department and the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University.

Like an anchor tenant, ElevateBio will lease about 70% of the site’s 175,000 square feet of space for what it calls a “BaseCamp” with facilities and capabilities that include gene editing; induced pluripotent stem cell; and cell, vector and protein engineering capabilities.

But the heart of Pitt’s BioForge will reside in the remaining square footage, Gabriel said.

The goal is to offer a battery of manufacturing techniques that can be applied to precision biological medicine, but the organization will intentionally be kept small, with about 10 to 15 BioForge employees.

That will be supplemented by researchers with some of the $658 million in NIH funding to Pitt who will come to BioForge for 18- to 36-month stints. They and their teams will be expected to actively participate in the work.

“They don’t get to throw it over the wall,” Gabriel said. “We’ll say, ‘If this is important to you, you’re gonna have skin in the game. You’re gonna bring faculty, postdocs, grad students, whatever it takes.’ ”

He alluded to a few early-stage projects that are underway. For now, he declined to provide specifics.

BioForge cannot control the market, but it can signal to the market that there are less expensive ways to manufacture, Gabriel said. That can nudge companies toward lower prices, be it thousand-dollar phones or cancer therapies.

“My argument — and it’s the same as with cellphones — is that you can reach a thousand investment bankers,” he said. “But you’ll make (vastly more money) if you can sell $100 or $200 cellphones to a billion people.

“That’s what I think the promise is here.”