As they have been for the past two months, and for more than four years before that, people who survived the 2018 mass shooting at the Squirrel Hill synagogue and those who lost family members there were resolute.

Filling three rows of seats behind the prosecutors who had advocated for them since long before the trial began, the loved ones of Joyce Fienberg, Richard Gottfried, Rose Mallinger, Jerry Rabinowitz, Cecil and David Rosenthal, Bernice and Sylvan Simon, Dan Stein, Melvin Wax and Irving Younger sat quietly.

Some clasped hands. Others clutched tissues, tears welling in their eyes.

They didn’t sob. They didn’t cheer or gloat.

Instead, they simply listened as the man who forever changed their lives and stole their sense of security — both in practicing their Jewish faith and in their city — received the death penalty.

The jurors, who had listened to nearly two months of grueling, graphic and often heartbreaking testimony, on Wednesday returned a unanimous verdict of death for Robert Bowers.

The panel deliberated for about 10 hours over two days — ultimately rejecting the central tenet of the defense that the killer is mentally ill.

It is the result that most of the victims’ families wanted, and one that prosecutors worked hard to earn.

A formal sentencing hearing will be held Thursday in front of U.S. District Judge Robert J. Colville. The judge is bound by the jury’s decision.

“This case at its core is about the victims,” said U.S. Attorney Eric Olshan, one of the lead prosecutors. “The ones who are no longer with us and the ones who have so bravely and gracefully carried the trauma of that day, every day since.

“This case has always been about those who survived and those who bear witness for the 11 who did not.”

Verdict handed down

Bowers, 50, of Baldwin was convicted of killing 11 Jewish congregants during his attack at the Tree of Life synagogue on Oct. 27, 2018.

The victims, who ranged in age from 54 to 97, were members of the Tree of Life-Or L’Simcha, Dor Hadash and New Light congregations, all of which worshipped at the synagogue on the corner of Wilkins and Shady avenues.

Jurors in June found Bowers guilty of all 63 counts against him and then in July said he was eligible for a possible death sentence.

Federal prosecutors believed that Bowers should pay for his crimes with his life, while the defense team asked jurors to spare their client, arguing that mental illness and a traumatic childhood meant he should not be subjected to capital punishment.

Word that a verdict had been reached started circulating around 11:15 a.m., and 25 minutes later, family members and friends began to file into the fifth-floor courtroom in the federal courthouse in Downtown Pittsburgh.

In the second row, Michele Rosenthal sat sandwiched between her sister, Diane Rosenthal, on the right and Carol Black on the left.

The Rosenthals’ brothers were killed. Black, who escaped the synagogue that morning, lost her brother, Richard Gottfried.

The three of them held hands, sitting quietly as they waited for the jury to return to the courtroom and during the 26 minutes it took for Colville to read the entirety of the verdict.

The defendant, dressed in a sweater and collared shirt like he has been every day of trial, sat quietly at the defense table between his public defenders, Michael Novara and Elisa Long.

Wearing reading glasses, he appeared to be reading along with the 26-page verdict form.

As expected, the jurors unanimously found all of the government’s aggravating factors applied to the case:

• That there were multiple victims.

• That the crime required substantial planning and premeditation.

• That he created a grave risk of others.

• That he expressed hatred and contempt toward Jews, which played a role in the crime.

• That he targeted the victims because they were Jewish.

• That he showed no remorse.

• That he caused serious physical and emotional injury to the other members of the synagogue and the police officers who responded that day.

Related:

• Timeline: Pittsburgh synagogue shooting case• Squirrel Hill holds complicated feelings about death penalty for synagogue shooter

• From 2018: 11 dead in shooting at Squirrel Hill synagogue

• More on the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting trial

The jurors didn’t agree on or accept each of the 115 mitigating factors listed by the defense.

They all agreed that Bowers’ mother was ill-equipped to be a parent and that he lived a troubled, chaotic childhood. They agreed that he was hospitalized for mental illness repeatedly.

But they disagreed whether he had a multigenerational family history of mental illness — only nine jurors found that a mitigating factor — and whether that family history put him at greater risk.

None of the jurors found that Bowers has schizophrenia or that he had brain abnormalities.

None of them agreed with the defense that he suffers from a mental disorder that has affected his life and behavior.

Then, at 12:15 p.m., Colville got to the portion of the form in which the jurors announced their verdict.

“We vote unanimously that Robert Bowers shall be sentenced to death separately as to each count,” it read.

Unlike in earlier phases of the trial, the 12 deliberating jurors showed no visible emotion as the verdict was read.

Bowers, as he has done throughout the trial, showed no reaction at all.

Colville thanked the jurors for their service, calling it a “great responsibility” and a “great burden to bear.” Appearing to choke up with his voice cracking slightly, the judge told the panel that he’d given the same speech to hundreds of juries over the years.

“I’ve never delivered it with as much sincerity as I did just now,” he said.

After the families had left the courtroom and were heading out of the hallway, Black remained.

Bowers’ aunt, Patricia Fine, approached her as she was leaving. The two women spoke briefly. From a distance, the words they exchanged appeared to be kind. Black smiled and nodded.

Bowers’ defense attorneys left the courthouse without comment.

U.S. Attorney Olshan spoke to reporters for several minutes, thanking the jury, law enforcement officers who responded that day and the investigators and prosecutors who worked on the case since.

But he focused primarily on the victims, recounting each of their names.

“The victims and family members have been a constant source of support and strength throughout the long road that has been this case,” he said. “They have been a valued presence in the courthouse every single day since the jury selection process started months ago. They have testified as witnesses in this trial. They shared their loss and pain, and their strength is an inspiration.”

Olshan said the evidence at trial proved that Bowers acted out of “white supremacist, antisemitic and bigoted views that, unfortunately, are not original or unique to him.

“Sadly, they are too common.”

Pittsburgh’s FBI Assistant Special Agent in Charge, Christopher Giordano, also addressed reporters.

“Today marks the end of one of the darkest chapters in the city’s history,” he said. “Today’s verdict will never bring back the 11 members of the synagogue who were killed, but to those families who lost loved ones, I hope today allows you to close this terrible chapter and continue moving forward and continue healing.”

A heart-wrenching 2 months

During the course of the long-awaited trial, which started in late May, jurors learned much about the lives of those killed and the impact of the crime.

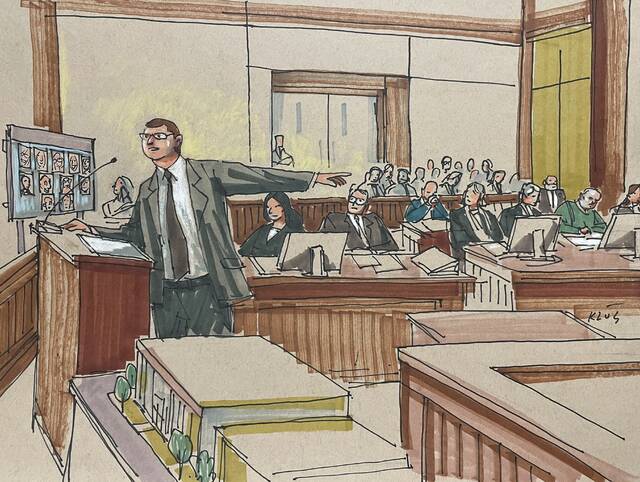

In their closing argument this week, prosecutors showed photos of the victims in life, smiling, surrounded by friends and family. They juxtaposed those with graphic images of where they were found on the day they died.

Margaret “Peg” Durachko told jurors about her late husband, Gottfried, who she met in dental school.

They later ran a North Hills dental practice, which she sold after his murder.

“It wasn’t any fun anymore to practice,” she said. “Half of me was gone.”

There were the Rosenthal “boys,” Cecil, 59, and David, 54. The neighborhood regulars — Cecil was sometimes known as “mayor of Squirrel Hill” — were born with intellectual disabilities as a result of Fragile X syndrome.

Their parents said the impact of their deaths is immeasurable.

“I woke up in the morning with two loving sons,” said Joy Rosenthal, their mother, in a recorded video. “I went to bed that night with only memories.”

Anthony Fienberg described his mom, Joyce Fienberg, as doting — “like Mary Poppins.”

“When I think back, she was our world. Our world revolved around her,” he said. “She was the guiding principle and, you could say, light when we were growing up.”

Throughout the trial, dozens of family members, friends and fellow congregants filled the courtroom.

Each day they took turns to allow new people to go inside, rotating among congregations depending on who was expected to testify. Family members could often be seen hugging in the hallways, holding hands in the courtroom and bowing their heads during painful parts of the trial such as when 911 calls were replayed or autopsy images were shown. Some even showed compassion to Fine, who attended most trial days and testified on her nephew’s behalf as the last defense witness.

Experts sparred throughout the course of the trial over whether Bowers was schizophrenic.

The defense team admitted extensive medical and hospitalization records, as well as psychological testing, showing their client had a chaotic and troubled childhood and serious struggles with his mental health.

One psychiatrist testified in the final phase of the trial that Bowers is schizophrenic and that his antisemitic beliefs were a product of religious delusions.

But a pair of prosecution experts said otherwise, discounting the schizophrenia diagnosis. They said Bowers never suffered from delusions.

During the eligibility phase of the trial, which primarily featured mental health testimony, it took the jury less than two hours to decide that Bowers was capable of forming the intent to kill — perhaps foreshadowing the ultimate outcome.

The case moved into the sentence-selection phase on July 17.

For the prosecution to obtain capital punishment, the jury needed to unanimously agree beyond a reasonable doubt that the nine aggravating factors outweighed any mitigating evidence. Although the defense offered the 115 mitigating factors, it wasn’t enough.

“Based on the jury’s apparent rejection of at least some of the psychological evidence offered as mitigation, it was the lack of a turning point that is most compelling,” said Bruce Antkowiak, a law professor at Saint Vincent College who followed the trial closely. “The horrific nature of the crime, the comments of the defendant thereafter, the lack of remorse and the devastating impact of the deaths on the community presented a difficult circumstance to mitigate.

“As earnestly as the defense put forth its case, the crime itself seemed to be overwhelming.”

Antkowiak said that the message sent in the jury’s verdict is clear.

“If we are to think of ourselves as a moral people, if we are to put an ultimate value upon anything, we must be able to say that under certain and indeed rare circumstances a line has been crossed which we cannot tolerate and cannot excuse,” Antkowiak said. “This jury has found that on Oct. 27, 2018, Robert Bowers took us to that line and crossed it.”

Ryan Deto and Stephanie Ritenbaugh contributed.