Luigi Lamendola had one of those colorful gangster nicknames. He was known as “Big Gorilla” because he stood 5-foot-8 and weighed 224 pounds. Few called him that to his face because he was a brute and a bully.

On a May evening in 1927, Lamendola came to the doorway of his Hill District speakeasy after two men tapped on the front window. Seconds later, shots were fired from behind the window curtains of a large touring car. According to a Pittsburgh Press report, the weapons fire “shattered” Lamendola’s head. Eight slugs lodged in his cranial cavity.

All signs pointed to a hit by the Monastero brothers, leaders of the largest gang on the North Side.

It sounds like a scene straight out of “The Untouchables,” though it didn’t happen in Chicago or New York City but rather on Chatham Street in Pittsburgh.

Some might say that Lamendola had it coming. He had helped to usher in Chicago-style violence in the Steel City by demanding that all other speakeasy owners buy their booze from him or risk being beaten or murdered.

The early days of Prohibition could be characterized as a thrilling game of hide and seek with police and politicians. Lamendola’s killing was an indication that the game had changed. There was now a violent battle among organized crime figures for control of the lucrative and illegal booze industry in Pittsburgh.

Prohibition was also directly responsible for decimating Pittsburgh’s legitimate whiskey industry, which had thrived prior to 1920.

Early years

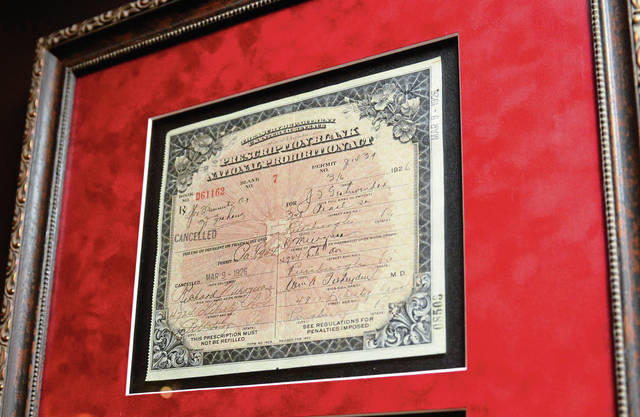

Prohibition, a nationwide constitutional ban on the production, importation, transportation and sale of alcoholic beverages, began to be enforced on Jan. 17, 1920. In the years before its passage, alcohol was seen as a destructive force that devastated American families and caused workplace accidents. Those who opposed it were called “wets.” Supporters were known as “drys.”

The law proved difficult to enforce, especially in Pittsburgh — where consumption of alcohol was an integral part of the culture of many citizens, many of whom were European immigrants who worked hard, built up the city and now called it home.

“The thing that surprised me about Prohibition were the people who simply ignored it,” said Leslie Przybylek, senior curator at the Heinz History Center who oversaw “American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition” when the exhibit traveled to Pittsburgh in 2018.

“There were some ethnic neighborhoods where it was not like people were purposely flouting it,” she said. “You weren’t going to go into parts of Homestead or Duquesne and find a lot of young women who were flappers. It’s just that drinking beer was part of their custom, and they simply didn’t stop.”

Not long after Prohibition started, Pittsburgh was declared the “the wettest spot in the United States” by Prohibition leaders in Washington.

Speakeasies, illicit establishments selling alcoholic beverages, proliferated in Pittsburgh. All the neighborhoods had them.

In the shadow of the old Pitt Theatre on Penn Avenue, Downtown, was a street referred to as Rum Row that sported eight speakeasies alone.

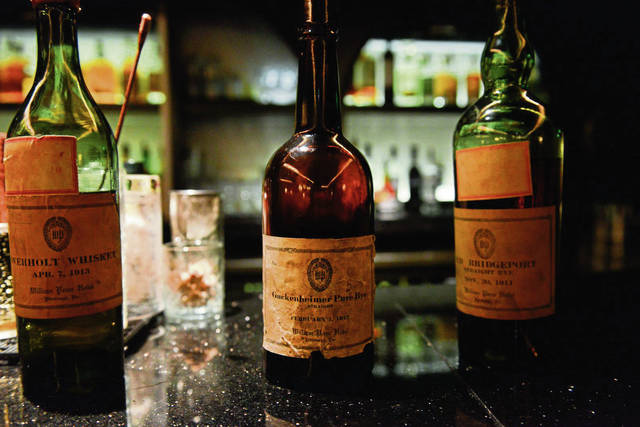

There was also a speakeasy in the basement of the William Penn, the grand Downtown hotel. It opened in 1920 when Prohibition began.

As was the custom with speakeasies, there was no signage. Patrons would knock on an unmarked door and have to be recognized by someone on the other side of a peephole or know a secret password to get in.

“Back in the day, it was so secretive but people knew they existed,” said Bob Page, director of sales and marketing for the Omni William Penn. “I’m sure there were a lot of payoffs that happened with the police to overlook a lot during the prevalence of speakeasies in the city.”

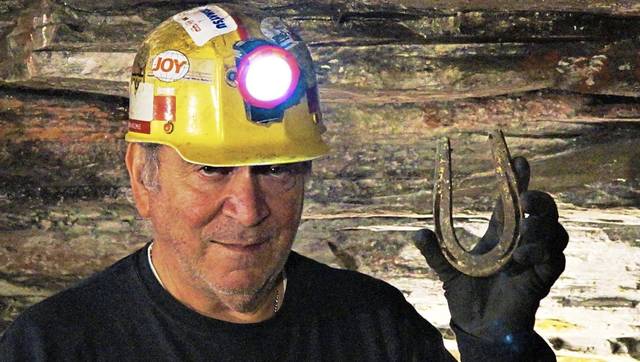

Page knows a lot about the room because it was unearthed around 1980 after being boarded up for nearly a half-century.

“When you walked into this room, you almost felt like it was an old Wild West saloon,” Page said. “There was a big mahogany bar, the floor was made of terra cotta and the wallpaper was beige felt with pink roses on it.”

It also had an escape route in case there was a raid — something almost every speakeasy experienced.

“We still have the one that was used here. There’s a hallway that goes along the front foundation of the hotel and it goes out through public space, and everybody would exit up the Oliver Avenue stairs.”

Feds send in heavy hitters

In addition to Prohibition being a law enforcement issue, it was a big political issue. Andrew Mellon, who partnered with Henry Clay Frick in the ownership of A. Overholt & Co. distillery and took control after Frick’s death in 1919, was secretary of the Treasury and therefore the chief enforcement officer for Prohibition.

Mellon sold Overholt & Co. to the Union Trust Co., of which he was a board member.

Eventually, undercover federal agents were brought to Pittsburgh to crack down on speakeasies. One of them was John Pennington, a former naval officer, who was conducting so many raids that corrupt politicians saw to it that he was transferred out of the city. Charles Kline, the mayor of Pittsburgh, had developed a business plan for political payoffs from bootleggers.

People became cynical.

“One of the things that you see over time is that people lose faith in the law when they see that there’s this huge divide in how it’s enforced,” Przybylek said. “While those who can afford it can stock up and go to their private clubs, there are those who say, ‘You are enforcing this law on the backs of the working class and not on the wealthy.’ So it becomes a perception of disparity in class among other things.”

Shootings in the streets

Between 1927 and 1932, war between gangs of bootleggers spread to the streets with murders and bombings that put Pittsburgh in the same league as Chicago and New York.

The clincher was the murder of the infamous Volpe brothers — John, James and Arthur. They were sons of Ignazio Volpe, an Italian immigrant who landed in New York in 1901. The brothers and their mother followed him to America years later.

The Volpes became fixtures in Wilmerding, where the family sold grapes and groceries and made wine. When Prohibition began, the brothers, led by John and James, sold lots of liquor. Their thriving business made them pillars of the community, and their ability to influence elections in Wilmerding’s 4th Ward enabled them to conduct their illegal activities without interference from the law.

In 1926, James Volpe was arrested for beating a Prohibition agent, who was left unconscious on a road outside the borough. Volpe avoided conviction, however. In fact, the brothers had avoided jail on a variety of charges — everything from selling liquor to kidnapping and murder.

By 1932, the Volpe clan had expanded their operations to Pittsburgh as part of a plan to “muscle in” on territory already controlled by other gangsters. After taking over the East End, they set their sights on Downtown, among other neighborhoods.

In a move reminiscent of Paul Muni’s “Scarface” character from the gangster film made that same year, John Volpe demanded other city racketeers adopt his price schedule. A gangster named John Bazzano ordered what turned out to be a very public hit on the Volpe brothers.

On Friday, July 29, 1932, hit men moved in on a coffee shop on Wylie Avenue in the Lower Hill District where John Volpe was meeting with his brothers. He walked back outside just as three men with pistols pulled up. John started to run toward his custom-designed light green, 16-cylinder Cadillac coupe, which had bulletproof glass. He was shot before he reached it.

Volpe died on the sidewalk. James and Arthur were shot dead in the coffee shop.

An edition of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph with a front-page picture of a bloody and dying John Volpe hit the streets after the murder.

“Pittsburgh didn’t have the level of violence that Chicago had, but this was probably as overt and famously tabloid as it got,” Przybylek said.

The Volpe killings brought the number of unsolved gang murders in the city to 100, The Pittsburgh Press reported at the time. By now, most everyone had had their fill of Prohibition.

Then and now

Prohibition ended in 1933. But not before it proved to be a major factor in the downfall of Pennsylvania’s whiskey industry.

Before Prohibition, Western Pennsylvania was one of the top producers of rye whiskey, churning out thousands of gallons per year. But Prohibition shut down most local distilleries.

“Following Prohibition, there was a lot of consolidation in the industry so you start seeing larger distilleries and businesses that are overseeing many conglomerates,” said Teresa DeFlitch, director of people and education at Pittsburgh-based Wigle Whiskey. “The smaller craft distilleries weren’t able to rebound after that. It took us a long time to get back up and running here in the city of Pittsburgh.”

In the past five to seven years, there has been tremendous growth in the local distilling industry — and Wigle has led the way. When it opened in the Strip District in 2011, Wigle became Pittsburgh’s first whiskey distillery since Prohibition.

“We opened because we wanted to bring back rye whiskey to Pennsylvania — that’s what Western Pennsylvania was known for,” said Mark Meyer, Wigle co-owner. “After Prohibition, there were probably two distilleries in the country making rye whiskey. That’s how consolidated it got because of what Prohibition had brought about.”

Wigle’s owners combined their effort with other emerging distilleries in the state to pass a bill allowing craft distilleries to sell their products on-site.

“That really helped get the craft spirits scene back up and running in Pennsylvania and here in Pittsburgh,” DeFlitch said.

Parts of Prohibition, however, are still felt today in Pennsylvania, which is known for having some of the strictest alcohol laws in the country.

When Prohibition was repealed in 1933 by the 21st Amendment, Pennsylvania Gov. Gifford Pinchot, whose “dry” stance was a factor in his election, pushed for strict regulations on alcohol. It’s why, decades later, customers in the Keystone State have to go to a state-run store to buy wine or liquor and a distributor, bar or brewery to purchase beer. Laws have loosened in recent years to allow some grocery stores and gas stations to sell beer and wine.

But a certain post-Prohibition nostalgia still prevails. Speakeasy-style bars have opened in Pittsburgh, including at the Omni William Penn.

“I think the allure is the room itself and knowing that this was a place in history,” Page said.

And no one has to worry about the police or feds raiding the joint.