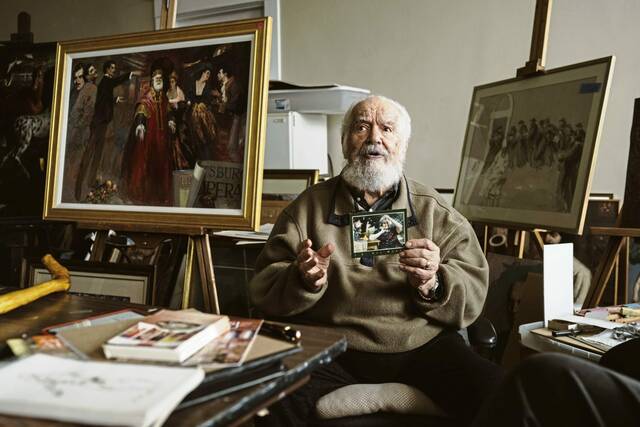

Surrounded by stacks of paintings and the pungent smell of turpentine, 99-year-old painter and art instructor John Del Monte moves his hand toward the top righthand corner of his sketchbook and marks a cross.

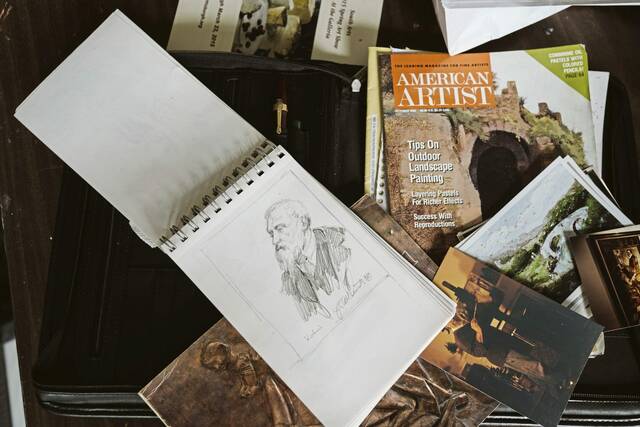

He stares at the two simple lines and rests his ink-coated hand on the studio table, which is covered in sketches and artist magazines. As he inhales, his white mustache quivers.

Del Monte furrows his bushy eyebrows in concentration and a flash of recognition passes over his eyes. He picks up his brown-ink pen, crouches closer to the page and resumes with fresh fervor.

Antonio Tavoletti, his 24-year-old grandson, loves hearing Del Monte describe this moment during his artistic process.

“When he’s at a spot in his painting where he doesn’t know what to do, he looks at (the cross), contemplates and lets his faith dictate what he’s going to be doing with his painting,” Tavoletti said.

Just as Del Monte relies on his faith to inspire the next paint stroke or sketched line, he uses his faith to dictate his next steps in life. This unwavering faith has brought him around the world, prompting him to open an art school in Lucca, Italy, with the hopes of making Europe accessible for small-town college students, and back to Pittsburgh in order to invest in family relationships and bring his lessons from Europe back to his hometown.

The painter’s gregarious love for life prompts many of his students to dub Del Monte not just a teacher of art, but a teacher of life.

Childhood

Del Monte grew up in a working-class neighborhood, McKees Rocks, to Italian immigrant parents who shared their Catholic faith with young John. But Catholicism wasn’t the only thing his parents brought over from the homeland. They instilled the Italian reverence for art in Del Monte.

He remembers his dad, an electrician by trade, standing on a chair and arching his back to trace the shadows and reflected light from the family’s chandelier on the ceiling, and then filling in and painting the design.

“A brilliant mind,” Del Monte said.

Despite his appreciation for art, Del Monte never took an art class and graduated from McKees Rocks High School in 1943 unsure of his next steps. He decided to enlist in the Navy as a typist and served as a second class yeoman in World War II. After the war, Del Monte used his G.I. benefits for art school.

Del Monte entered the art classroom after WWII much like Robert Rauschenberg, a painter and sculptor well known for his work “Combines,” and Roy Lichtenstein, an American pop artist.

Rejected from his first choice — Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University, where he would later work as an art professor — Del Monte was not deterred. He applied to the Art Institute of Pittsburgh and studied commercial art, focusing on magazines and illustrations.

He accepted his first job in the industry and remembers working on a painting for a menswear ad when an adviser recommended he include fewer folds in the right sleeve. Indignant, Del Monte refused to compromise his art.

“You know what I did?” he recalled. “I got up from my chair, and I said, ‘Get somebody else to do this!’”

His boss at the ad agency attempted to do the illustration himself, only for the client to reject the piece.

“I was happy as a lark,” Del Monte said.

The entire interaction left a sour taste in Del Monte’s mouth, however, and he decided he needed to leave Pittsburgh.

“Risk is very important,” he said.

He applied for a scholarship at the Art Students League, and moved to New York in the early 1950s and stayed there for seven years. Eventually, even the Big Apple started to feel too confining for Del Monte, so he applied for a scholarship to study in Cape Cod before proceeding to work as an art instructor at multiple institutions.

In 1953, he spent eight months in Europe enamored by his role models. He drooled at masterpieces by Rembrandt, John Singer Sargent and Leonardo da Vinci, and found inspiration in the Italian countryside.

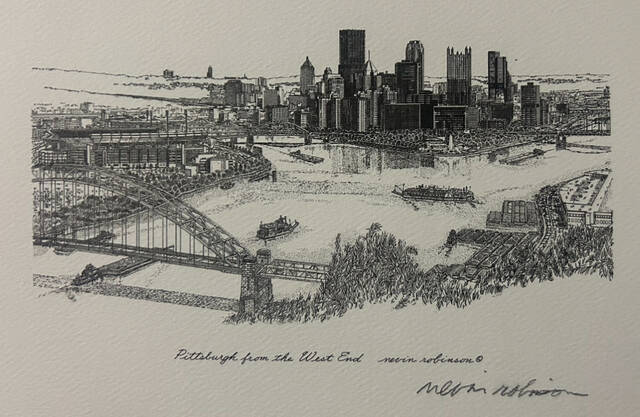

While in the Netherlands, Del Monte was commissioned to illustrate the cover of “For Esmé — with Love and Squalor” by J.D. Salinger. After experiencing immense inspiration and artistic success in Europe, he felt the urge to share the joy with others and a dream was born: start an art school in Italy for young artists so they, too, could experience the inspiration of Europe.

In the interim, Del Monte started teaching art at Carnegie Tech, and plans for the art school took the back burner.

Starting a family

In 1962, John and Jean Del Monte eloped in Assisi, Italy, and spent eight months traveling around Europe.

Claudia Brehse, Del Monte’s youngest daughter, describes her parents as opposites who complement one another. Her mother, a former student of Del Monte’s, was always willing to help Del Monte accomplish his artistic pursuits.

“You know how they say behind every great man is a woman?” Brehse said. “She quit her job, and she cooked three meals a day and cleaned the house so he had his time to paint. She was super supportive that way.”

Jean Del Monte often obliged her husband’s artistic visions, dressing up as the Virgin Mary in their front lawn so he could take photos and conduct a study for future paintings. When John wanted to paint Westerns, he would pose on a saddle on the living room couch and his wife would take photos for reference. Brehse remembers her father dressing up in pilgrim boots and knickers to pick her up from school.

“Growing up, it was mortifying,” Brehse said.

In retrospect, however, she cherishes her childhood as the daughter of an artist. While other kids had normal paintings of ships or landscapes, her house was decorated with her father’s surreal paintings of flying bishops and horses.

She remembers her dad encouraging her to play with her food, coaxing her to imagine vivid scenes out of leftovers. She would hesitantly move the food around on her plate, and suddenly pine trees by the lake would form out of peas and gravy.

Brehse inherited her father’s creativity and teaches middle school art in Hudson Valley, New York. She never understood why her father didn’t accept offers to move abroad or consider moving to Italy full-time.

As a child, she desperately wanted to leave Pittsburgh behind. As an adult, however, she realizes that for her father, family was treasured and he wanted to stay close to relatives in Pittsburgh.

Brehse was also shaped by her father’s faith.

“My dad has had a huge influence on me as far as the spiritual world is concerned,” she said.

She remembers going to church with her father before the family experienced a falling out with the church leaders. In her second grade CCD class, Brehse asked if Adam and Eve looked like cave people, and the nun declared her question blasphemous and sent her to the priest’s office.

“My dad came to pick me up and said, ‘Let’s talk about this,’ but the priest kept his mouth shut and didn’t even look at my dad. So my dad took my hand and we walked out,” Brehse said.

Disagreements with the local Catholic parish never dimmed Del Monte’s Christian faith . He tries to read his Bible every morning and has a list of people he says his prayers for daily.

“I think that’s where his positivity comes from, that belief to always find the best in any situation,” Brehse said.

Creative art studies in Lucca

When Del Monte was laid off from Carnegie Mellon, despite students fighting for him to stay, he decided to consider the setback an opportunity to unabashedly pursue plans for the art school. Soon after, he met the mayor of Lucca, who was visiting Pittsburgh at the time, and the mayor promised to help Del Monte set up an art school by providing a new bus and setting up shows for student work.

In 1969, this dream became a reality and Del Monte opened Creative Arts Studies in Lucca .

Former student Ron Donoughe considers his trip to Italy in 1979 life-changing. Del Monte’s formal training in anatomy and color theory from his days at the Art Students League in New York dazzled the self-described Indiana University of Pennsylvania “hillbilly.”

“It was like magic,” he said.

Del Monte introduced students to Italian culture, taking students on day trips to local restaurants where they could share their art, and to Carrara, Tuscany, to chat with modern-day workers at the quarry where the marble for Michelangelo’s David was excavated.

“He really did teach us about doing what you love everyday and making the most of your life,” Donoughe said.

Donoughe was inspired by the seriousness with which Del Monte approached art. When students and staff went out to explore the town at night, Del Monte would often stay in his studio working on new art pieces.

“John was a worker,” Donoughe said. “He put the time in, and he taught us you can have fun, but still be serious about what you’re doing.”

Reflecting on the experience, Donoughe believes he left with the spirit of Del Monte more than his teachings.

“He was the priest, the president and the CEO of the whole operation,” Donoughe said. “He was a spiritual leader in how he conducted the program.”

John Bell attended the program the same year as Donoughe. Due to Del Monte’s fluency with the town and its culture, the students were able to become a part of the community for the summer. Del Monte was asked to talk to news outlets and give critical opinions about what was going on in the town.

“I tend to be introverted, so in a lot of ways I admire people like Del Monte,” Bell said. “I wish I could be more like him.”

During those joyful summers spent teaching and enjoying the company of friends in backyards and kitchens, Del Monte painted one of the favorite paintings of his career.

His students often ate their meals at the restaurant of a woman named Barsati who made “very good spinach,” according to Del Monte. One day, she invited his students to her house to make pizza and drink wine, and Del Monte saw her sitting outside, shading her eyes from the sun.

He grabbed his camera and took her photo. Later, he painted the scene and gifted the painting to Barsati’s restaurant, where it still hangs today.

Most of Del Monte’s works hang in private collections or churches. His favorites remain with him in his studio, above a local coffee shop.

Del Monte’s studio

Del Monte enjoys spending time in his studio on the second floor of the Schoolhouse Arts and History Center in Bethel Park. Del Monte used to teach art lessons for South Arts Pittsburgh, a nonprofit group, on the first floor. But when Del Monte was 93, his landlord moved him upstairs and Reginald’s, a new coffee shop, moved in. The shift came with a caveat of promising to install an elevator.

Six years later, Del Monte, who is 99, still has to hold onto the railing and the arm of his grandson or daughter in order to access his top-floor studio.

Coffee shop visitors today might enter and exit the schoolhouse never knowing Del Monte was busy sketching upstairs, or view him as an old, if interesting, conversationalist. Most don’t know a 99-year-old painter with failing eyesight is quietly sketching abstract drawings.

Del Monte has diabetic retinopathy, damage to the retina caused by having too much sugar in the blood. In later stages of the disease, blood vessels in the retina start to bleed into the vitreous, causing the afflicted to see dark, floating spots or streaks of brown that look like cobwebs. Without treatment, scars can form in the back of the eye, according to the National Eye Institute.

Tavoletti has watched his grandfather’s eyesight and ability to paint deteriorate over the past two years. Del Monte started as a realist, moving into surrealism in his mid-age, and then back to realism and portraiture in his later years. Unable to continue in his previous styles, he wasn’t sure how to continue making art.

His daughter, Brehse, recommended he begin experimenting with abstract drawings.

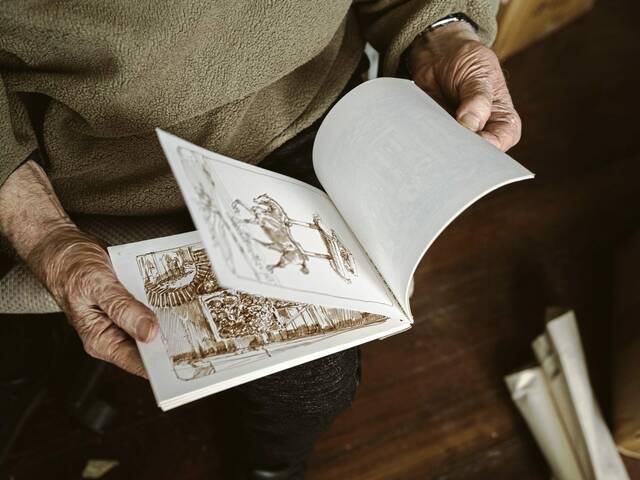

Like Claude Monet, who developed his distinct style in the French impressionist movement due to cataracts in his later career, Del Monte started to experiment with his style and shifted toward line drawings — abstract sketches made with thick black pen on white paper, as his eyesight worsened.

“They’re really cool,” Brehse said. “You can look at it and each person interprets it in a different way. I see this or that or that. He’s still got it.”

Del Monte says his best thoughts now come while lying down.

“I see the pen going in such a way and then I change it and try it this way, and do it another way, and eventually I get something that’s pleasant,” Del Monte said, flipping through his sketchbook.

Tavoletti said his grandfather doesn’t like talking about his move to the abstract, and doesn’t feel the need to explain what he’s drawing or why. Tavoletti thinks it’s a way to keep making art, no matter what.

As a photographer, Tavoletti relates to his grandfather’s need to create.

“It’s an itch I’ve got to scratch,” he said.

He was inspired to make art from a young age after spending time in Del Monte’s studio. He compares his grandfather’s art collection to a family album — a familiar, comforting presence. Sometimes Tavoletti will grab a coffee downstairs and then sit in his grandfather’s studio and stare at the paintings.

“It’s more impactful than I can articulate in words,” he said.

Art ties Del Monte’s family together. All of his kids and grandkids have picked a medium for themselves, just as John did. Reflecting on his most meaningful painting, Del Monte gestured to his right.

The looming painting rests near the doorway of the studio and features Del Monte’s late father sitting on a chair surrounded by a cloud of white, meant to symbolize the Holy Spirit, with two horses to his left. The surrealist painting demands attention and nods to the man who all those years ago inspired Del Monte to create, while tracing the shadows of the chandelier onto the ceiling.

“The painting was displayed at my father’s funeral, and I hope it will be displayed at mine, as well,” Del Monte said.