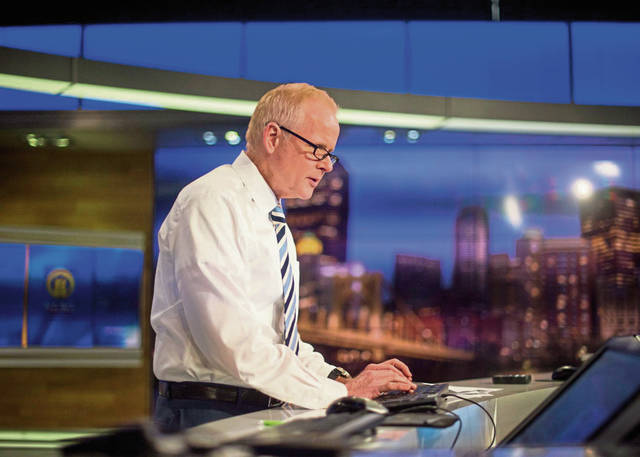

KDKA Meteorologist Ron Smiley typically takes to Twitter early each week to share a social media video of the seven-day snow forecast.

About 3 a.m. Monday, he was a little hesitant.

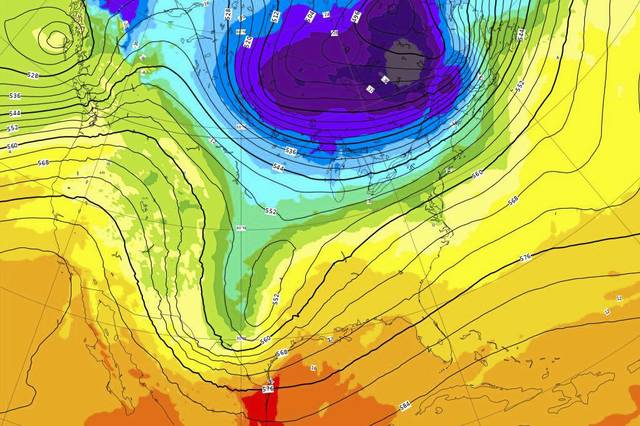

“I almost don’t even want to do it because of how big these totals are that are coming in,” Smiley said in this week’s video, which included a weather model showing the Pittsburgh region receiving up to 16 inches of snow through Sunday night.

At this point, that’s all it is: a model.

The “Snowpocalypse 2019” storm supposedly barrelling toward Western Pennsylvania is a rather small blip on a very large map. It will need to get a lot closer before local meteorologists can get a better sense of what it will leave behind.

“No matter what you’re forecasting for, you’re looking at all the data you can possibly find,” said Scott Harbaugh, a meteorologist with Tribune-Review news partner WPXI-TV in Pittsburgh. “There isn’t much data right now because this storm is out in the Pacific.”

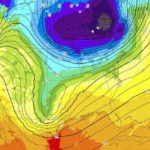

Much of the data being used to forecast the coming snow involves various weather models, which slap physics on current weather observations to create a picture of the atmosphere and how it will behave. There is an American model, a European model, a Canadian model and so forth.

“Different models take in different data sets and come up with their initial picture in a different way,” said meteorologist Matthew Kramar, who works in the National Weather Service office in Moon.

The American model is generated by the NWS’s Environmental Modeling Center in Washington, D.C., but Kramar said NWS officials are not partial to one model over others.

“The forecast process is a lot of analysis,” he said. “We want to see which models are showing the current situation the best.”

Weather forecasters compare models to real-time weather conditions to see which is the most accurate.

“If you can’t trust the current picture, how can you trust what it’s predicting will happen four days from now?” Kramar asked.

The primary differences between the American and European models lie in data simulation, computing power and the physics used, according to Scientific American magazine. In 2012, the European model predicted the devastation caused by Hurricane Sandy — which included more than 200 deaths and $75 billion in damage — much more accurately than the American model, which forecasted the storm fizzling out over the Atlantic Ocean.

Both the American and European models generally are used to make long-term predictions.

Also impacting prediction of how a storm will track and how severe it will be is the fact that existing weather is already making its way across the country.

“We have this other weather system coming in before the weekend storm, and it has to be developed before we can figure out exactly what’s happening with that little blip out in the Pacific Ocean,” Kramar said.

Harbaugh agreed.

“What each (weather) system does is lay down a path for the next system,” he said. “The system we had (Wednesday) morning that brought freezing drizzle? That wasn’t on the table on (Tuesday) morning. But now that we’ve had that, it tells me we had warm air aloft, so my gut tells me that there will still be enough warm air aloft that the rain line could push up into Pittsburgh (Thursday.)”

Rain in advance of the weekend could have a strong effect on the coming snow.

One thing is for sure, Harbaugh said: Storms like the one developing in the Pacific want to find cold air, and the weather Thursday night into Friday will go a long way toward creating a more accurate picture of what’s to come.

Kramar said current models showed two relatively consistent outcomes for the weekend — one in which the Pittsburgh region gets 2 to 5 inches of snow “and another much higher.”

“There’s a lot more confidence right now in a larger amount of snow in northern Pennsylvania, near the lakes,” he said. “But one of those models has shown a shift south in those larger snow amounts.”

The next 24 to 36 hours will provide a lot of the information that will help solidify a forecast.

“We need to see what happens with the storm system (Thursday) night, and then we can get a better picture of the weekend system,” Harbaugh said.

Patrick Varine is a Tribune-Review staff writer. You can contact Patrick at 724-850-2862, pvarine@tribweb.com or via Twitter @MurrysvilleStar.