Kim Ward didn’t want anyone to know.

When the state Senate majority leader from Hempfield was diagnosed with breast cancer in November 2020, she told almost no one.

Not her staff. Not her friends. Not even her mom.

When she went for chemotherapy at the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Unity, the nurses allowed her to slip through the back door instead of walking through the lobby where the 16-year senator might run into someone who recognized her.

And when faced with the prospect of going bald because of the toxic chemicals that would help save her life, she fought that off, too, choosing to use a cold cap to try to save her hair.

It wasn’t until Ward was through the chemo — and heading toward a double mastectomy — that she went public.

Within months of successfully completing her treatment — and based on her own experiences with gaps in insurance coverage and testing requirements — Ward set out to improve the system that sees 14,000 Pennsylvania women diagnosed with breast cancer each year.

And she did, earning unanimous, bipartisan passage of Act 1 in spring 2023.

The legislation mandates free breast MRIs, ultrasounds and genetic testing for people at high risk who are covered under state-regulated insurance — as many as 3 million Pennsylvanians.

And Ward says she isn’t done. Each year, the Republican Senate president pro tempore attends multiple breast cancer awareness events across the state, conducts media interviews and contributes to a digital public service campaign. During the month of October — Breast Cancer Awareness month — the message is even more intense.

“I got what I needed, but everybody needs to get what they need,” she said. “Every single woman, every single mom.

“Everybody needs to be able to get the best treatment — and as early as possible.”

Diagnosis

It was 2020, and the covid-19 pandemic was in full force.

With much of life shut down, Ward, then 64, said she was about six months behind in having her mammogram. With dense, fibrous breasts — which can make it more difficult to detect a tumor — she had been having the test done annually since she was 36.

There was a spot, she said, a calcification.

Ward had a biopsy that day in December.

A tumor, 1.8 centimeters around, had popped out of a milk duct in Ward’s left breast.

It was Stage 1 invasive ductal carcinoma — the most common form of breast cancer, accounting for about 80% of cases, said Dr. Shannon Puhalla, a medical oncologist who treated Ward at the cancer center in Westmoreland County.

Ward’s cancer, which was estrogen receptor positive, had lobular features, making it more likely to have a recurrence in 10 or 15 years, said Dr. Terry Evans, a medical oncologist at the Unity site for the Hillman Cancer Center. Ward had a lumpectomy nine days after she got the biopsy back and testing in her lymph nodes showed that the cancer had not spread, Evans said.

But a MammaPrint — a test that examines breast cancer tissue — showed Ward was at high risk for later developing metastases, or the cancer spreading, Evans said.

Her team of doctors debated the need for chemotherapy, with one doctor suggesting it was unnecessary and another urging her to have it.

Ward, a 5-foot-tall spitfire of a woman, chose to have chemo.

“I talked to my family, and they’re like, ‘Just do it. That way you know you’ve done everything you can possibly do,’” she said. “So I did it. It was scary. And then I remember after my first chemo treatment saying, ‘That’s it?’ ”

‘I was fine’

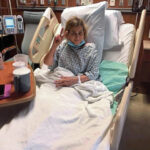

On Feb. 4, 2021, Ward and her husband, Tom Ward, arrived at the Arnold Palmer Pavilion in Unity for her first chemotherapy session.

To help pass the time, she took her iPad and cellphone to do work. She also had an electric blanket and a big blue slushy from Sheetz.

Ward took a cooler of dry ice for her cold cap. Tom’s job, in addition to keeping his wife company, was to change her caps every 20 minutes.

The caps narrow the blood vessels in the skin of the scalp to try to prevent chemotherapy drugs from entering the hair follicles, according to breastcancer.org. It was not commonly used at the time in this particular office and was not covered by insurance. But, for Ward, saving her hair was a priority, so she happily spent the $1,800 to do it.

“That meant everything to me as a woman, to be able to not have anybody feel sorry for me,” she said. “Because that’s what I would have gotten in Harrisburg. ‘Are you OK? Are you OK?’

“I was fine.”

Ward kept her hair, having only a small section impacted over the course of her chemo.

She approached her treatment with purpose, did her own research — reading medical journals, not just Googling terms — and became her own best advocate.

“She made it her mission to learn everything you possibly could know about breast cancer,” Tom said.

Even though he’s a physician, he said his wife’s knowledge of her disease went much deeper than his.

“She took it on like she approaches everything else — tireless,” her husband said.

Ward had four cycles of chemotherapy over 12 weeks. She received her chemo on Thursdays — after legislative session days in Harrisburg, which are normally Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday — so that she could be back to work after the weekend without missing a beat. As an early riser, Ward’s work day starts between 4 and 5 a.m. and frequently continues long into the evening.

“She fought through it,” said her husband of 42 years. “She wasn’t going to let it slow her down.”

After her treatments, Ward would return to her Hempfield home to rest, work and play with her grandchildren.

Her son, Michael, regularly left bags of red and black licorice on her pillow. He also took drinks to her with ginger, which can help combat nausea during chemo, even though Ward said her side effects were minimal.

Her son, Matthew, was living in Chicago and constantly called and messaged to check on Ward, while her son, Tom, frequently brought over the grandkids, now 6, 4 and 2.

He remembers his mom remaining steady throughout her diagnosis and treatment, even when the family was worried, and especially before she got her prognosis.

“It was a pretty terrible couple months,” Tom said, his voice breaking. “You automatically think of all the things you could have done differently. You worry your kids won’t remember her.

“That was really the worst part, thinking my kids wouldn’t know her.”

But Ward remained resolute.

“It was really unnerving,” said her son, Tom, 41, of Greensburg. “She handled it better than me.”

As her first rounds of chemo were underway, Ward sought to have testing to determine whether she had a mutation in her breast cancer — or BRCA — genes.

BRCA tests can help predict whether a woman is likely to develop breast cancer later because women with a mutation are at much higher risk. But Ward learned that her insurance wouldn’t cover a BRCA test. They told her she was too old at 64.

“‘But it’s not about me,’” she told them. “‘It’s about my kids, my grandkids.’”

Ward had sought one even before she was diagnosed but was rejected then, too. Although her maternal grandmother and three great-aunts all had breast cancer, she said the insurance company denied the request because it wasn’t her mother or sister.

Ward paid the few hundred dollars for the test herself.

On March 1, 2021, she got the results: She had the BRCA mutation.

Ward scheduled a double mastectomy for eight weeks after her last chemotherapy treatment on April 4, 2021.

On June 28, 2021, as she waited at UPMC Magee Womens Hospital to go into surgery, Ward posted a video to Twitter with her son, Michael. In it, she urged her constituents to be vigilant in their breast care and screenings.

“I guess it’s tata to my ta-tas,” she said, signing off.

Ward’s recovery went smoothly, and she ultimately had reconstruction, including having new nipples made from her own tissue.

A couple of months after her mastectomy, Ward also had a hysterectomy to further lessen her chances of recurrence.

After her surgeries, Ward’s mom spent a lot of time taking care of her — including shuttling her to medical appointments and cooking. One of her favorite meals is spaghetti and meatballs, said her mom, Joanna Renko.

“What I saw from her was determination,” said Renko, 85, of Chartiers. “She handled it her way and nobody else’s.”

At the time, in August 2021, state government was still dealing with the covid-19 pandemic, demands for a mask mandate in public schools and calls for an audit of the 2020 presidential election.

Even as Ward recovered, Renko said her daughter was constantly on the phone working.

Ward’s husband said the same.

“When it comes down to it, you can have all the support in the world, but the fight is your own,” he said.

Recovery

Ward isn’t shy anymore about her diagnosis or treatment.

Or the results of it.

If someone asks about her surgeries, Ward, whose personality is forthright and funny, has been known to slide her blouse and bra out of the way and show the results of the reconstruction.

Marc Gergely, a former state representative who served with Ward for years in the Pennsylvania House, ran into her at a Kentucky Derby event in 2022 in Washington County. His wife recently had been diagnosed with breast cancer, gotten through her chemo — including using cold caps — and was facing the prospect of surgery.

Ward showed him her chest.

“It’s what the surgery looks like for a normal woman,” Gergely said Ward told him. She told him that his wife’s life had been saved, and if she needed to have surgery, it would be OK, he recalled.

“‘I’m fine. I’m still a woman, and she will be, too,’” was the message, Gergely said. “She was being very positive.”

Ward is happy to talk to anyone about her experience — even strangers who stop her in the grocery store, which happens frequently, she said.

“Even if I’m in a hurry, when those folks start talking to me, I want to hear the story,” she said. “I just slow down and listen. Because it helps me, and it might help them.”

She called it therapy.

Ward’s experiences, her husband said, gave her added purpose in life.

“She came out of it stronger and determined to help other people,” he said.

Ward’s message to others: “It’s a scary thing to have to go through. But you’re alive.”

‘Early detection saves lives’

As Ward made her way through testing and treatments — including being denied insurance coverage for the BRCA test — she saw gaps in the health care system.

A woman with connections and power, Ward was able to advocate for herself and get the information she needed. But not everyone has the same ability or resources, she said.

Ward decided to fix that. She began working with Pat Halpin-Murphy, president and founder of the PA Breast Cancer Coalition, to figure out what they might be able to change together at the state level.

Halpin-Murphy had been diagnosed with Stage 3 breast cancer in 1993. After undergoing aggressive treatment, she beat the disease and dedicated herself to helping others.

In Ward, she found an ally.

Following an event to turn the Capitol Fountain in Harrisburg pink in October 2022, the two returned to Ward’s Senate office to talk.

“She was very concerned that women have access to genetic testing and counseling and MRIs and ultrasounds [for dense breasts],” Halpin-Murphy said.

That day, the two hashed out — in broad strokes, at least — what legislation could look like.

Less than six months later, it passed the state Senate unanimously.

“She was determined that women would have access to these life-saving tests in this state,” Halpin-Murphy said. “Early detection saves lives.”

The bill had momentum going into the state House, she said, and passed there unanimously as well.

The support was so profound, Ward said, because so many people are impacted by the disease. Statistics show that 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer.

On May 1, 2023, it was the first piece of legislation Gov. Josh Shapiro signed in his tenure.

“None of that could have happened without the leadership of Sen. Kim Ward,” Halpin-Murphy said.

With the new law, Pennsylvania became the first state in the nation to require insurers to provide no-cost breast MRIs, ultrasound and genetic testing for high-risk women — which includes those with family history, dense breast tissue and previous abnormal screenings.

Breast MRIs can cost anywhere from $300 to $4,800, according to the coalition. Many people can’t afford such expensive testing, and so they forgo it. If they have breast cancer, it may not be found until later, often making treatment more complex.

Over the last year, Halpin-Murphy said her office has gotten about 300 calls from women seeking to take advantage of the change in the law.

The coalition is now working, along with Ward’s help, to spread the message. The senator has cut commercials and public service announcements, held mammogram drives with mobile screening units and talked to various groups about breast screening.

They estimate they’ve reached millions of women.

“What a gift that is to them and their families,” Halpin-Murphy said.

Looking forward

As Ward continues on her mission to help others fighting cancer, she said there is more work to do.

Among the topics she is considering for additional action in Harrisburg: whether women who test positive for the BRCA gene will still have access to affordable life insurance and health insurance.

Ward said she also expects to work on legislation addressing testing needs for other kinds of cancer.

“I think there’s more we can do, and we’re going to keep looking and talking to folks that have experienced things and trying to help people,” she said. “If we do nothing else in government, we should be trying to help people on a level that we can.”

Editor’s note: Reporter Paula Reed Ward is not related to Sen. Kim Ward.